A classic narrative arc played itself out in Canadian publishing this month: good triumphed over evil. The Canadian government, suddenly and inexplicably, slashed its funding for the Literary Press Group — an organization that distributes and promotes most Canadian-published books. The funding cut would have crippled not only the LPG, but close to 50 publishers and all of their authors. But people successfully petitioned against it, and the Minister of Canadian Heritage restored funding for the LPG. It was an amazing, uplifting example of the power of the people, and I would hope, restored a sense of pride and value in Canadian publishing companies.

But there’s a lesson to be learned here. We need the government to value Canadian publishing houses, and calling them “small presses” is not helping that cause. Whether you know it or not, what we mean by “a small press” is “q Canadian press publishing Canadian authors.” The other guys, the “big publishers,” like Random House and Penguin and HarperCollins, they’re not Canadian owned, and they’re the publishing equivalent of a Wal-Mart set up beside a boutique shop. I have no prejudice against “big publishers,” but more often than not, the books I love come from a Canadian “small press” like, most recently, Cormorant Books (via And Also Sharks), Douglas & McIntyre (via Radio Belly), and Biblioasis (via Malarky). This article begs you get your mind out of the gutter: bigger isn’t better.

Assuming big internationals produce higher quality books is statistically false

Yes, let’s just come right out and say it: there are many small Canadian presses that are a joke — they’re run on grants they don’t deserve, and they do nothing for the authors of their poorly edited, atrociously designed, crappily written, and virtually not-marketed books. This article ignores them.

I’m talking about the GOOD Canadian presses, and they’re far too numerous to list, and being that my background is science, I know real proof isn’t in persuasive writing, but, rather, numbers and facts.

Here are some facts:

Randomly selected, recent awards shortlists dominated by Canadian indie presses:

Italics: Canadian indie presses / Regular: Big international presses

This year’s Trillium Award for Best Book Out of Ontario

The Methodist Hatchet (Anansi)

The Free World (HarperCollins)

Idaho Winter (ECW)

And Me Among Them (Freehand)

The Perfect Order of Things (Thomas Allen)

Phil Hall (Book Thug)

This year’s Thomas Head Raddall Shortlist (A 20K prize for the Best Book by an Atlantic Canadian):

The Lightning Field by Heather Jessup (Gaspereau)

Tide Road by Valerie Compton (Goose Lane)

An Incident in the Life of Dean Markus (Random House)

The last two Giller Prizes combined:

Half-blood blues

The Free World

The Antagonist

The Sisters Brothers

Better Living Through Plastic Explosives

The Cat’s Cradle

Annabel

The Sentimentalists

Light Lifting

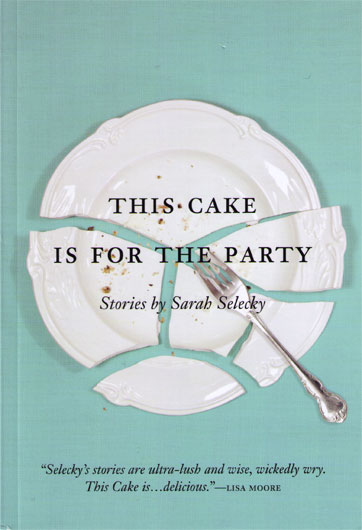

This Cake Is For The Party

The Matter With Morris

This year’s finalist for the International Commonwealth Book Prize (Canadian and European Category)

The Town That Drowned (Goose Lane)

This year’s Danuta Gleed Winner for Best First Book of Shorts

Not Anyone’s Anything (Freehand Books)

Is your pride and confidence in CANADIAN publishers flaring? Is the term “small press” seeming more degrading, or at least more like a good thing? Small means selective, not inferior. So start calling them Canadian presses, not small presses.

“Small press” only means quality over quantity, since when is that bad?

Canadian presses like Coach House Books and Pedlar Press don’t produce as many books a year as Random House or Penguin, so we call them “small.” But since when is quality over quantity a bad thing?

Publishing fewer books a year forces Canadian publishers to be selective and publish only what they love, and what fits their “brand” or preference. This approach gives weight to their company logo, and an astute Canadian reader like me can come to trust that logo as I would a line of clothes or a winery whose products I know I like. A “big” multinational book factory like Random House or Penguin? Not so much. They publish books by the truckload, and it’s certainly not all Canadian-authored books. By publishing fewer books, Canadian publishers let you keep up with the books they are deeming the cream of Canada’s crop.

These big internationals? Well, just go on their websites and try and browse for a book you like.

Random House’s hip fiction title by a Canadian right now is A Magnified World by Grace O’Connell. But you click their “New Fiction” buttons and it’s easily missed (proof). It’s buried under a pile of commercial fiction, of no interest to me, and largely not written by Canadian authors. I am not knocking Random House so much as I am illustrating a flaw in being a “big publisher.” Go to Goose Lane’s website, they’re Canada’s oldest independent publisher, and have a look at how easy it is to find new books of interest to you on a Canadian press’s website. And note how much more excitement they’re able to build around their books, and how much more info they can relay by publishing and maintaining promotion around fewer titles. Their ability to do so is an asset in getting Canadian books into Canadian readers’ hands.

Small Canadian presses are not stepping stones to bigger houses: They’re the victims of huge international corporations buying out our big authors

I come from Newfoundland — that place with all the fish, all the big and fresh and world-renowned fish, whose history is defined by the depletion of those fish by foreign countries coming over and taking some of those away from us. In my analogy, these Big Fish are the big-named Canadian authors that bigger international houses, on Canadian soil, can lure away from Canadian presses by baiting a hook with a book deal our writers can’t afford to turn down. It doesn’t make them a better publisher, it makes them a richer one. Alternatively, many of our writers choose to publish with the big guys because of the prestige of their logo and a shot at more media attention. Neither decision to publish with “the Big Six” is a reflection of the quality of a book … yet the word “small press” feels like little league. The minors. And my colour-coded guide to recent awards begs to differ.

There’s an assumption the quality bar is set higher to be published by a “big publisher.” That’s not the case: Russell Wangersky and Lisa Moore are two Canadian authors whose sentence-level writing is a God-given gift us mere mortals couldn’t emulate if we tried. They publish with Thomas Allen and Anansi respectively. Breakwater Books in Newfoundland are publishing some of my favourite Newfoundland writers, Like Samuel Martin and Patrick Warner. Douglas & McIntyre are reliably publishing our freshest new voices like Matthew J. Trafford and Nicole Lundrigan. My point is, “small” Canadian presses are the ones pumping out the fresh, vibrant, highly readable new face of CanLit. The big multinationals everyone so reveres? They might have the money to reel in the big-named authors, but those big-named authors bore the pants off me as a rule, and they sell copies on the weight of their names as much as their books. Bigger presses do not mean better books. I’ve been reading long enough to be damn sure of that. Yes, they publish some great novels, but certainly no more than their Canadian “small press” counterparts. And they certainly publish as many duds.

Plea to media

Get over logos. Assign reviews and coverage based on author bios or how well the first page of a book reads. Support your local publishers and Canadian publishing. I recently reviewed The Sometimes Lake, by Thistledown Press, for the Telegraph-Journal. I really wasn’t expecting it to be some of the best short fiction I’ve read in the last year or two. And that’s the thing. Every year another handful of Canadian presses impress me with the integrity of the books they’re publishing. Most recently: Thistledown, NeWest, and Freehand. And every year, ones like ECW and Breakwater just get stronger and stronger.

Moral of the story

Get as excited about Canadian books as the people working at Canadian publishers. Visit their websites. Because trust me and my 500-book bookcase: they’re the best. To ensure our Canadian publishers and associates like LPG continue getting their funding, we need to instill a sense of value and importance to Canadian literature, so please don’t call Canadian publishers “small presses,” call them Canadian presses. Call them what they are: amazing, yours. And read them widely and often. Get your minds out of the gutter — bigger isn’t better, it’s just bigger, and that comes with flaws. And while it’s fodder for an entirely different article, there’s reasons for writers to publish with Canadian small presses over the big guns. Many. Example: most awards, like the Giller, only let you submit 3 to 6 novels per publisher. “Big publishers” publish a lot more than 5 novels a year. Who do you think they’ll submit, you or Ondatjee and Munro?

When we heard the bad news about LPG’s funding cuts this month, we should have been saying, “what a blow to Canadian publishing.” Not, “what a blow to small presses.” I couldn’t help thinking, Maybe if you’d all stop calling them “small presses” and stop thinking of them as stepping stones to the big international publishers like Random House the stigma of inferiority would vanish and their perception by government would be one of value.

This article originally appeared here, on Chad Pelley’s blog Something Daily.