Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporting member of rabble.ca.

James Laxer is a professor of political science in the Department of Equity Studies at York University. He is the author of A House Divided: Watching America’s Descent into Civil Conflict, a House of Anansi Digital Publication.

On July 1, 1863, 150 years ago last Monday, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, 70,000 strong, Robert E. Lee commanding, encountered Union forces on the outskirts of Gettysburg in the rolling hills of southern Pennsylvania.Union Gen. John Buford‘s force of 2,500 cavalrymen set itself up on the western edge of the town on Seminary Ridge, named for the handsome Lutheran Seminary that stood there. Buford knew that Confederate forces were closing in on his position from the west and the north.

The clash that commenced on July 1 endured for three days. It was the fiercest single battle in a war that took the lives of 600,000 men. Forty thousand Canadians enlisted in the Union army over the course of the war.

Four years to the day after fighting at Gettysburg erupted, Canadian Confederation came into being. The battle and the new country were intimately linked.

During the 1860s, the adherents of three national projects engaged in a desperate struggle for chunks of the North American continent. There was the northern project, led by Abraham Lincoln; the southern project whose leader was Jefferson Davis; and the Canadian project, squired by John A. Macdonald.

In the years before the guns boomed south of the border in 1861, Canada, a union of anglophone and francophone societies uncomfortably wedded in a single province, descended into political deadlock. Unless the leaders of the province could find a new formula for the union of its two peoples, Canada could not hope to become the hub for the construction of a transcontinental state.

The war that erupted between North and South in April 1861 focused the minds of political leaders in Canada and the Atlantic provinces, who feared that they could be drawn into the war as a result of tensions between the North and Great Britain.

With a total population of 3 million by the 1860s, equivalent to that of the 13 colonies when they declared their independence from Great Britain in 1776, the British North American provinces could be seen as well positioned to launch a country of their own within the British Empire. But not only was the Province of Canada geographically remote from the Atlantic provinces, its internal politics was at an impasse due to the conflict between its French and English inhabitants.

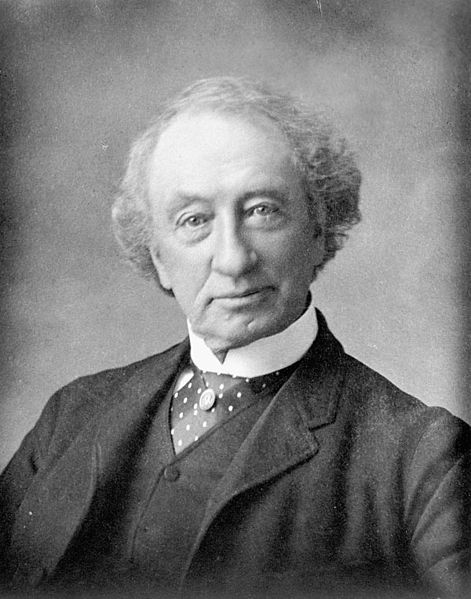

Finding the key to resolving that deadlock, let alone pursuing the dream of British North American union, would require political leadership of the highest order. Fortunately for British North Americans, they had in their midst a political leader as shrewd and far-sighted as any in the history of the continent in the person of John A. Macdonald.

Flawed by his bouts of alcoholism, his willingness to ride roughshod over the Métis and First Nations peoples, and his penchant for corruption — he was an inveterate supporter of crony capitalism — acdonald’s genius was easily overlooked.

The American Civil War motivated leaders who loathed each other — John A. Macdonald and his nemesis, George Brown, leader of the Reform party (Liberals) — to form the great coalition, along with French Canadian George-Etienne Cartier, that was needed to establish a country. There was only one chance to create a federation that had the potential to span the continent and Macdonald and the others took it in the greatest high-stakes gamble in Canadian history.

What Canadians of later generations often failed to understand about the genius of Confederation was that it was both a coming together and a separation. The splitting of the Province of Canada into its two halves, Ontario and Quebec, which meant that French Canadians would govern a major province, made possible the success of the wider union, first with the Maritimes and then the West. Macdonald was the architect of this settlement of the English-French question in his day.

British North Americans were not mere bystanders in the conflict to the south. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, British North America was a partner in the reciprocity (free trade) agreement with the United States that had been negotiated by London and Washington. Reciprocity, which came into effect in 1854, changed the pattern of trade between the United States and the British provinces to the north. Primary products, especially forest products, flowed south and finished goods were shipped north. An acute observer looking at Canadian affairs on the eve of the Civil War could reasonably conclude that the colonies north of the United States were en route from a British to an American connection, that the fate of Texas would soon be the fate of northerners.

That observer would have been wrong. The great conflict in the United States threw the absorption of Canadians into the American sphere off course. Acute tension between the United States and Britain during the war provoked Washington to formally abrogate the Reciprocity Treaty by invoking its two-year cancellation clause.

Not only did the Civil War pose a direct military threat to Canada, it derailed the economic strategy of the British North American provinces. Canadian political leaders needed a wholly new approach to cope with the crisis that confronted them.

Remarkably, they rose to the challenge.

It was Macdonald who presided over the completion of Confederation, the creation of a transcontinental Dominion, and the building of the railway that gave it life. Many decades would pass before Macdonald’s country would gain control of its foreign and defence policies. And much more time would be required before Canada — its enduring problems, between English and French, and the third world status of native peoples notwithstanding — became recognized universally as one of the most successful human habitats on the planet.

Though people don’t usually think of it that way, Canada Day celebrations and commemorations of the battle of Gettysburg are both rooted in the great upheavals of the 1860s.