The 2012 London Olympics mark the first time that the quadrennial celebration of athletics (and cold hard cash) will include women’s boxing as a medal sport. As one might expect, this has led to plenty of publicity around the event, from a feature in The New Yorker to Cover Girl ads. What this coverage shares is a fundamentally celebratory tone. The inclusion of women’s boxing is read as another important step for the women’s movement.

This is a very tempting narrative. It is inequitable for Olympic events such as boxing to feature only male eligibility. Likewise, it has been a struggle to achieve recognition and inclusion. In short, the idea of jumping on this bandwagon is awfully appealing. Except that, this triumphalist discourse happens to obfuscate some significant issues around gender, race, class, and, perhaps, most of all, violence.

Women’s boxing as feminist project

In order to unpack what I mean, let us turn to the aforementioned piece in the May 2012 issue of The New Yorker penned by Ariel Levy and entitled, “A Ring of One’s Own: A teen-age Olympic boxing hopeful.” The article chronicles the meteoric rise of 17-year-old U.S. boxing aspirant Claressa Shields, taking us through her successful journey to the U.S. Olympic Trials. Levy portrays Shields as a gifted and driven young woman who seems equally bent on winning gold and busting stereotypical attitudes about women and women’s boxing.

Levy’s article is marked by the sort of triumphalism I referenced above. Early on, Shields describes why she, at age 11, wanted to begin boxing, suggesting it was to follow in her father’s footsteps: “He said, ‘H, no! Boxing is a man’s sport.’ I just started crying. I didn’t talk to him for two days. After he told me no, that kind of motivated me, really, just to prove him wrong,’” (pp. 40-41). This is the seed of what will become a sort of feminist kunstlerroman, the story of a girl who is able to live her ceiling-busting athletic dream.

Levy provides examples of the misogynistic culture Shields is up against, telling us that trainer Tommy Gallagher sees women’s boxing as “wrong and unnatural,” that Joyce Carol Oates called boxing “‘the obverse of the feminine…[it is] for men, and is about men, and is men,’ and that New York Times sportswriter Robert Lipsyte referred to women’s boxing as “‘a freak show,’” (p. 41). In much the same vein, he goes on to catalogue the history of women boxers, producing a sort of genealogy that becomes more of a teleology in the context of Shields’ rise.

The teleological nature of this narrative is driven home by powerful quotations from Christy Halbert, a sociology PhD on the International Boxing Association’s Women’s Commission, and from Shields herself. Halbert explains that boxing, like other sports, does not allow women to play in exactly the same way as men. In boxing, this is because women have shorter fights (four two-minute rounds instead of three three-minute rounds). Halbert explains the difference this way: “‘Because what if the women are better at this event than the men?’ she replied. ‘What does that mean for gender? What does that mean for men’s power?’” (p. 43). This is a thoughtful and compelling case. Shields adds: “‘It just hit me. The reason that I box is to prove dudes, men wrong. They say women can’t box?… I’m finna [fixing to] start training so hard there’s no male can even see a mistake in me,’” (Ibid.).

I don’t question the feminist bona fides of either of these women. Halbert connects patriarchy to boxing in an incisive way. Shields proves that challenging gender inequity is at the forefront of her own project. Both of these women deserve to be lauded. Indeed, the article ends with Shields describing her beloved coach as “a male chauvinist,” (p. 47). The problem with Levy’s article — and the broader discourse that it represents in its most self-reflective and refined form — is what it fails to sufficiently foreground about the politics of boxing.

Is women’s boxing liberation?

The first issue to address, in peeling back the laudatory veneer of women’s boxing as liberation, is the precise nature of that liberation. That is, we need to examine exactly what kind of feminist project this is. Despite the protestations of Halbert, who seems concerned with actually interrogating the very notion of gender and its relation to structures of power (for which I applaud her), this is much more of a second wave project aimed at achieving institutional equality. Again, women should have institutional equality. The question is whether that is enough.

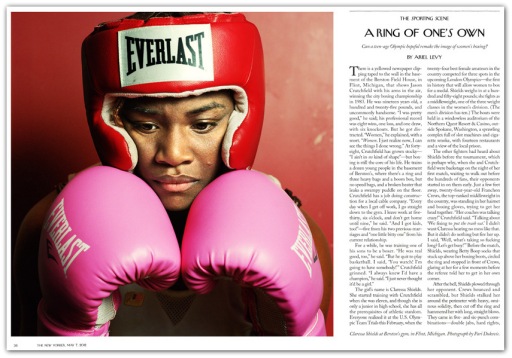

The picture of Shields used to introduce the article shows her gazing contemplatively downward while leaning her face on her boxing gloves, which sit in the foreground of the image. This is unremarkable, except for the fact that the gloves are bright pink. Soon after, still on the first page of the piece, Levy informs us that when he meets Shields before a match, she is “wearing Betty Boop socks that stuck up above her boxing boots,” (p. 39). Indeed, Shields’ trainer tells us, “‘She’s real emotional–yeah!’ He laughed. ‘A sixteen-year-old! You’ve got to deal with the boys! You’ve got to deal with the up and down and all around! Oh, man! I mean, this has been hell for me!’” (p. 40). As difficult as he finds it, “this is not to say he wants Shields to appear unfeminine. She told [Levy], ‘I was going to come here with an Afro, but people’ — she indicated [her trainer] with her eyes — ‘got stuff to say about that.’ He had directed her instead to get the long braided extensions she was wearing. ‘She has a real good personality,’ [her trainer] explained. ‘So I want her to have the appearance to go with it — ‘Oh, hey, she looks nice and she talks nice,’” (p. 46).

New Yorker photographer Pari Dubovic is sure to capture Claressa Shields’ pink boxing gloves for this feature piece by Ariel Levy.

What all of these examples reveal is the way in which Shields is gendered. Her ability to challenge the glass ceiling of boxing has had little to no effect on the expectation she fulfil her designated gender role. She must appear feminine in order to have public appeal. That is, she must be objectified as a sex object as much as an athlete. Moreover, she is still perceived through the lens of gender essentialism; as a woman, her trainer tells us, she is “emotional.” His job, as patriarch, is to regulate her sexuality.

Shields is not the only boxer subject to this gender surveillance. Another U.S. Olympic representative, Marlen Esparza, remarks, “‘When people say, “You don’t look like a boxer,” I’m like, “Thank you!”‘ she said. ‘It sucks whenever I want to wear a strapless shirt or a dress. My shoulders look all strong.’” Evidently, she has internalized the expectations that have been placed on her, struggling to fulfil them by appearing in a Cover Girl campaign with Canadian boxing champion Mary Spencer (see the above link) in which they flaunt their femininity, ostensibly in their athletic apparel, yet, meticulously made up, styled, and groomed. It is little wonder, then, that although many members of the women’s boxing community are openly gay, they are forced to grapple with the perception that they are “‘brutish’” “‘bull dykes,’” (p. 45). In fact, the president of USA Boxing, Hal Adonis, says that although he has no problem with homosexuality, “‘Only thing is I don’t want to see — we had a situation with one of the girls, she was on the elevator kissing her girlfriend…we have a public image. We don’t want to have, when we’re trying to get girls into the sport, their mothers saying, “Gee, I don’t want my girl to be around your gay girls because they might try to make her gay,”‘” (Ibid.).

Much as we might want to believe it is, this is not a community that represents liberation for women. It is a world where gender norms are clutched all the tighter for fear they might slip away in a sea of sweat and blood. There is a form of feminism at work here, just not the robust form required to push for profound structural change.

Race, class, violence and boxing

Although my preoccupation to this point has been with the extent to which women’s boxing may or may not be perceived as a feminist project, this is actually not the most fundamental problem I see with the triumphalist discourse associated with its inclusion in the Olympics. What I want to take greater issue with is the endorsement it provides for the sport of boxing itself. For, the most equitable development that could occur within the world of boxing is its outright abolition. To put it as concisely as possible, boxing is an exploitative and dehumanizing spectacle. This fact is not the fault of boxers, and so I celebrate the women who have finally received deserving recognition for their labour. It is, however, the fault of institutions like the Olympics, which have simply found a new way to cash in.

Boxing, like other sports, draws heavily for participation upon the most disadvantaged groups of society. Poor and racialized youth, with few opportunities for economic and social advancement in an American society that relies upon their insecure socio-economic position for cheap labour, come to see sports like boxing as a way out. The intense brutality of the sport is much less of an inhibition for those who face such conditions in their everyday lives. Again, Levy’s article — and Shields’ life story — provides a neat lens for examining the matrix of race, class, and violence that comprise the structural context of boxing. Levy writes (and I quote at length here because of the salience of this passage):

“Clarence Shields has been an important but intermittent figure in his daughter’s life. ‘I’d go two, three months without seeing him,’ Claressa told me. ‘Then I’d call and he’d be like, “Oh, what’s up, Muffin?” I’d be like, “How come we never see you?” “Oh, I don’t like y’all coming around here when we ain’t got no money.” I was like, “We already living in poverty, and you’re just making it harder.”‘ Broken stoplights dangle over many of the intersections in Flint. Most of the streets have boarded-up houses, like the one next to Clarence’s home, and the town is patched with blacktopped expanses where Chevrolet and Buick factories used to be. When Jason Crutchfield drove me through the abandoned downtown, under the ‘Flint–Vehicle City’ arch on Saginaw Street, he said, ‘I remember my grandmother walking me through here. It used to be packed.’ Both Crutchfield and Shields have relatives who worked in the auto industry, and their fathers both spent time in prison after it disappeared. Clarence Shields did seven years for breaking and entering.”

The context for Shields’ boxing career is not just some innate passion for her father’s sport. It is intimately connected to the political economy into which she was born. The destructive effects of globalization upon the U.S. auto industry; the consequent formation of a rust belt of hollowed out former metropolises with few sources of employment; the ghettoization of urban cores due to white flight and redlining practices; all these factors, not to mention earlier histories of accumulation and dispossession due to colonialism, slavery, and capitalism frame the range of possibilities Shields was born into. Growing up in Flint, Michigan, in a racialized community in an urban ghetto in the heart of the rust belt, few choices were available to her. The appeal of a sport that might allow her to fight her way out is not hard to imagine.

Flint, MI, is one of America’s most infamous examples of urban poverty and decay. (Photo: Brian Finoki.)

Indeed, it is precisely those who experience the most extreme forms of violence and abuse (above and beyond poverty and racialization, although, no doubt, associated with the desperation they cause) who are most susceptible to the sport. Levy writes of USA Boxing president Adonis, “Adonis himself was qualified to box because ‘my father invented child abuse,’ he said, with an incongruous smile. ‘I learned how to play chess when I was six years old. My father would have a strap and smack me across the face if I made the wrong move. So when I got onto the streets and got into boxing, I was so used to getting hit it was like, ‘Hey, this is nothing!’ When he trained kids, he said, ‘before a fight I’d start smacking them real hard in the face. Because you feel, in boxing, the first couple punches. After that, the endorphins kick in and it’s like someone gave you Novocain,’” (p. 44).

There is something fundamentally diseased about a sport that requires abuse as a form of high-performance training. Yet, it is logical that it would, given the damage boxers inflict upon one another over the course of a typical fight. Studies associated with another, comparatively less violent sport, football, suggest that concussions cause significant long term harm, even if the short term effects seem manageable. The very premise of boxing is to inflict so much damage on the opponent that they are unable to continue. Nevertheless, the defence is often offered that at least boxing (and other violent sports, such as football) offers some form of hope for those with few other sources of opportunity. But does it really, or is this hope it provides really something quite a bit more illusory?

Levy’s story helps us answer this question. Writing of one of Shields’ teammates, Tyrieshia Douglas of Baltimore, Levy says, “Just after she won the semifinals of her division, we spoke outside the ballroom. ‘I don’t get paid,’ she said. ‘I don’t have nowhere to go. This right here is my ticket out.’ Douglas, who has a wiry frame and a sweet face, grew up in foster care while her parents were in and out of prison. She got into boxing through a compulsory community-service program after she broke one girl’s jaw and another’s nose in a street fight. ‘My dream was to finish high school, to go to college, take care of my mom, my daddy, and my brothers. I stopped going to college for boxing. I gave up everything,’ she said, choking back tears. ‘No one’s taking my ticket. No one’s taking my last piece of chicken.’ She walked away, crying.”

Later, we learn that Douglas does not make the Olympic team. She has nothing to show for her efforts. Young racialized aspirants like Douglas and Shields are told that boxing offers them a way out of the ghetto. They are told to eschew education and other avenues of personal development in order to concentrate on the sport. Yet, the probability that a pot of gold awaits at the end of the rainbow is infinitesimally smaller than the reality that all they will be left with is a damaged body and a battered brain.

There is no simple solution. The eradication of boxing will not solve the structural issues that plague our world. It will not end patriarchy or the objectification of women, nor will it equitably redistribute wealth or abolish racialization. These are all projects that we must pursue more broadly if we want to live in a just world where Tyrieshia Douglas and Claressa Shields have a fair chance. What such a step will accomplish is end the propagation of false hopes and dreams, aspirations that fuel the corporate machine that is the Olympics.

Nathan Kalman-Lamb is a PhD Candidate at York University in Toronto and is the co-author (with Gamal Abdel-Shehid) of Out of Left Field: Social Inequality and Sports.

*The full quote reads as follows: “In the center of the room, Crutchfield [Shields’ trainer] was watching two boys sparring in the ring. ‘Put your hands up, fool! It’s time to man up!’ he yelled at the one who was getting cornered. ‘He hitting like a girl!’” (p. 47).