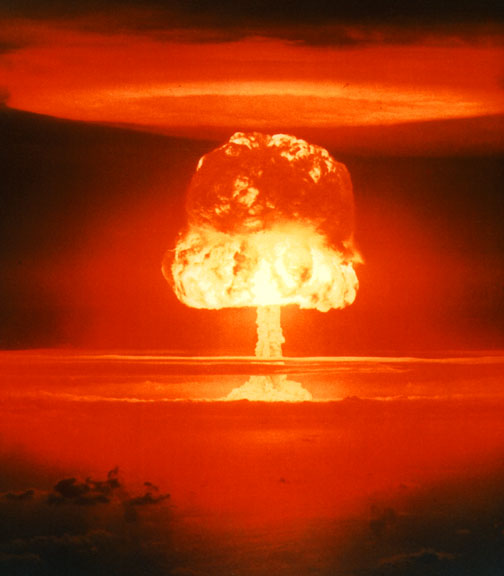

Crave privacy in a crowded world where your every move is being watched? Want to lead a secret life? Next time round, come back as a Bomb. Not any old bomb but the big one, the nuclear kind. Here’s the proof — and don’t dismiss it as mere history.

On January 23, 1961 a B-52 took off from a base in North Carolina on an airborne alert, flying a long circular route over the American east coast. At almost midnight, after more than ten hours in the air, after flying its second loop, and after its second refueling in the air, fuel began leaking badly from the plane’s right wing. Instructed from the ground to dump the remaining fuel in the ocean and prepare for emergency landing, the crew discovered that the fuel wouldn’t drain from the left wing, creating a dangerous weight imbalance. At half past midnight the plane went into an uncontrollable spin. The crew bailed out as the plane started to break apart at an altitude of ten thousand feet. Of the eight man crew, five survived and three died.

There were two hydrogen bombs on that plane. One fell free of the plane and hit the ground near Faro, North Carolina. It had a number of safety mechanisms. It did not detonate but every safety mechanism but the final one had failed. The second bomb penetrated more than seventy feet into soggy ground; a recovery team never found it.

Had the first bomb detonated, it “would have deposited lethal fallout over Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City.”

This we now learn fifty years later from an encyclopedic hair-raising book, Command and Control, by the American writer Eric Schlosser, on nuclear bomb accidents. (Quotations are from the book.) At the time, in a bare-faced assertion of lies, “The Air Force assured the public that the two weapons had been unarmed and that there was never any risk of a nuclear explosion.”

It so happened that this almost-catastrophic accident took place three days after the inauguration of John F. Kennedy in Washington. His inaugural address, still ringing in the air, had been full of eloquent optimistic rhetoric about America’s glorious future. Robert McNamara, the new Secretary of Defense, committed to making rational decisions based on careful cost-benefit analysis, learned of the accident on that third day and Schollser tells that it “scared the hell out of him.” But not enough for him to share that story and his feelings with the rest of us, who just might have set up a clamour for abolition of this terrible weapon.

Three years later there was the well known Cuban missile crisis that did truly scare people like myself who were alive back then and did lead to more insistence on arms control. But the point of Schlosser’s book is that the 1961 scare, and others he tells us about, were just as scary but we never heard of them.

We talk a lot now, as we properly should, about the need for more transparency and a deeper democracy. But, as many writers have noted, nothing has ever been created so destructive of democracy as the Bomb. That in itself should be sufficient grounds for its abolition. It breeds and feeds authoritarianism — up to the person with the finger on the launch button with merely seconds to make a decision.

It was born and built in the U.S. during the Second World War in such secrecy that the American public knew nothing of it and the Canadian public knew nothing of our role as supplier of uranium for atomic bombs. Even heir-apparent vice-president Harry Truman knew nothing until Roosevelt died and as president he was let in on the secret — while, in contrast, Stalin with his spies was remarkably well informed on an on-going basis.

But is this not now history? The Cold War which the Bomb fueled is over and that is good news indeed, but we did not take advantage of that fortuitous event — in spite of the support of no less a person than American President Ronald Reagan as the Cold began to thaw and War disappeared as an option — to try to rid the world of nuclear weapons. Actual nuclear war is still a possibility between, say, India and Pakistan, but even if we judge its occurrence there or elsewhere to be improbable, the main message of this book is that accidents can happen and there always could be one that we learn about the hard way, by being blown to kingdom come.

So take a moment off from fighting climate change, and other things that frighten us, and speak out for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Image: Wikimedia Commons