There is some discussion in Nova Scotia about the possibility of the government introducing a carbon tax in the next budget. In this blog post I will introduce the context within which these discussions are taking place, and make reference to other blog posts in this forum that provide insights into how the province might best approach a carbon tax policy.

First, I believe Nova Scotia’s low-carbon transition does not receive the attention it deserves. The province is expected to generate 25 per cent of its electricity from renewables in 2015, and has a target of 40 per cent by 2020 (largely due to plans to import hydroelectricity from Newfoundland and Labrador). The province has become a leader in energy efficiency, led by Canada’s only non-profit “energy efficiency utility.” It has also introduced hard caps on GHG emissions from the electricity sector. Much is made of Ontario’s dramatic reductions from the phase-out of coal-fired electricity, but Nova Scotia has made similar percentage reductions since 2005. Nova Scotia’s emissions reductions are driven by policies that can put the province on the path towards even lower emissions. (In contrast, New Brunswick’s large decrease seems to be mostly due to higher oil prices reducing electricity exports from an oil-fired power plant). (Of course I have to admit my bias here, since I was involved in N.S. energy policy during the introduction of many of these policies, as a consultant or environmental advocate).

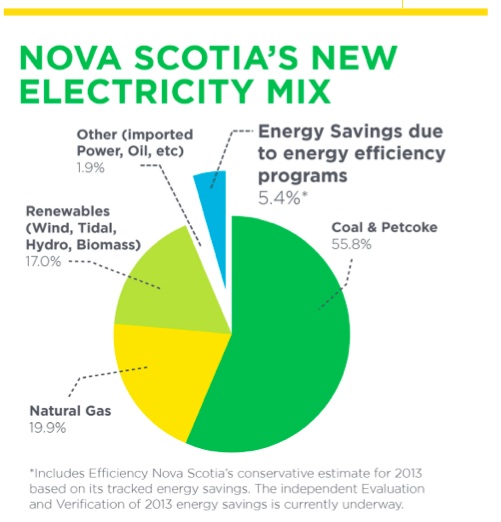

Nova Scotia’s example is important to the rest of Canada because it is a carbon-intensive province, with an electricity system based on coal, undergoing a significant energy transition. Many of the other progressive climate policies in Canada come from the less carbon-intensive provinces of Ontario, Québec, British Columbia, and Manitoba. If Nova Scotia were to implement a carbon tax it would fit nicely with its existing policy mix and contribute to a real transition away from fossil fuels towards more a more efficient and clean energy system.

The idea of a carbon tax or other form of pollution tax came from a report written by former Ontario cabinet minister, and new Nova Scotia resident, Laurel Broten. Her review of the tax system recommends a carbon tax that is “revenue-neutral,” with revenue earmarked for low-income support as well as corporate and personal income tax cuts.

Broten points towards the success of B.C.’s carbon tax. As demonstrated by Sustainable Prosperity, B.C.’s carbon tax has decreased emissions. The predictions that the tax would harm the B.C. economy have also not come true. B.C.’s GDP growth, relative to the rest of Canada, has been largely unaffected by the tax. The report also notes that recycling the revenues of the B.C. carbon tax towards tax cuts means that B.C. has some of the country’s lowest personal income and corporate taxes.

While one cannot claim that B.C.’s carbon tax has harmed the economy, nor is it possible to claim that these lower tax rates have helped it. As noted by Jim Stanford’s recent blog post, B.C. is not a bastion of economic prosperity (measured by GDP per capita) or social welfare (the province has below average per capita spending on health, education, and social assistance).

In Nova Scotia, the larger economic context is important to consider in the carbon tax discussions. A year ago a “Commission on Building Our New Economy” (also called the Ivany Commission after its chair) authored a report called “Now or Never.” The report sounded an alarm bell on the province’s economic situation and called for a “province-building” project. The Commission report cast a wide net and could be used to justify anything. The commission supported the province’s continued transition towards a green economy. Some in the province have used the Commission’s message to call for government downsizing, austerity, and tax cuts. Hence, the interest in the “revenue neutral” carbon tax seems to be linked to some people’s interpretation of the Commission’s message.

Nova Scotians would do well to consider Marc Lee’s case against a revenue-neutral carbon tax. Lee notes that there is little evidence that personal income tax reductions benefit the economy by increasing the incentive to work. Even in neoclassical theory the economic impact of a tax cut is ambiguous because the increase in real personal income could make people engage in more leisure. Practically, there are a number of structural issues that make it hard for people to increase their hours of work on the margin, as suggested by neoclassical theory.

In Atlantic Canada there is the traditional issue of people “Going down the Road” to find work in other parts of Canada. But this is not because of a lack of incentives to work instead of engaging in leisure. It is because of a lack of job opportunities. As well, corporate tax reductions seem to only be contributing to cash hoarding by corporations, and not encouraging investment (See Erin Weir). So an industrial attraction and innovation strategy cannot rely on tax incentives.

So here are some takeaway lessons as Nova Scotia considers implementing a carbon tax. First, such a tax will help decrease GHG emissions and hopefully complement other climate change and energy policies in the province. Second, if what is really needed is a “province-building” project, it makes sense for Nova Scotia citizens to have a fuller discussion on how the carbon tax revenue could be used for this purpose. For instance, the tax revenues could be used in a targeted way to facilitate an industrial transformation towards a green economy, to increase community innovation and economic development initiatives, and to enhance energy security by accelerating the move away from imported fossil fuels with more energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Stay tuned to see what happens in Nova Scotia.