Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Everybody seems to have a theory about Brexit and I am no exception.

Britain was never in Europe entirely. It is a long tortuous history from the beginning of the Common Market to now but it goes back much further than that. I don’t suppose it’s too big a stretch to say that the original invasions of Great Britain from Europe were all part of an effort to bring the islands together with the mainland.

Over the years the British, despite the occasional common monarchy, thoroughly mistrusted the French more than that they saw economic advantages in any union. Oddly enough, Britain’s only enduring alliance with Europe is with Portugal, going back to 1386.

Churchill’s ‘New Europe’

It was after two massive wars in the twentieth century that spawned the idea of peace through economic arrangements and there are many who credit Churchill as the author, arising out of his famous speech in Zürich in 1948 where he called for a united states of Europe.

Not for the only time in his career he was badly “non” quoted because after he spoke of united states of Europe, he said these words:

“Great Britain, the British Commonwealth of Nations, mighty America, and I trust Soviet Russia — for then indeed all would be well — must be the friends and sponsors of the new Europe and must champion its right to live and shine.”

Churchill long nurtured the notion of the English-speaking world and saw not only the political connections as important but also free trade arrangements which had been augmented over the years. He certainly saw no reason to sacrifice those arrangements to the uncertainty of a European market full of countries Britain had mostly been at war with and few of which it had strong trade relations with.

A common market

From the outset, the Labour and Conservative Parties were each divided on this issue and the divisions in some cases ran very deep. For the average Briton, the overriding feature was the avoidance of yet another bloodbath and the coming together of France and Germany, originally in a Coal/Steel Pact, went a long way toward solving the problem.

The notion originally sold to Brits was a “common market” not a political union. In fact the political operation was pretty loose with an unelected executive in one city and a toothless parliament in another. The executive wielded most of the power and was unaccountable to the public.

Politicizing the union

As matters progressed, the European centrists eased into a not-terribly subtle process of politicizing the union without saying so. The history of this starts with one Jacques Delors.

However much Britain may have accepted membership in what was to become the EU, there were everyday irritations which probably need not have taken place. One might find, for example, that the garden hose they had to buy didn’t fit the British faucet and things of that nature. These piss-offs didn’t kill the EU but they certainly did nothing to inspire affection.

Jacques Delors became the President of the European Commission in January 1985, laying the groundwork for single market within the European Community, which came into effect on 1 January 1993. There was no public vote to ratify this new arrangement.

Thatcher and co. push back

In the autumn of 1988, Delors addressed the British Trade Union Congress, announcing that EC would force the U.K. to bring in pro-labour legislation. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher responded with her famous “Bruges Speech” on September 20, 1988, where she said that she had “not rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain only to see them reimposed by a Brussels superstate.”

The fat was in the fire. Whereas, as recently as the early 1980s, much of the Labour Party had opposed the EC, while the Conservatives had favoured joining, after 1988 it was to be the Conservatives who were divided, with Thatcher and her supporters opposed to further European integration.

Delors bore the brunt of British Euroscepticism. This was best exemplified by The Sun‘s headline on November 1, 1990 reading, “Up Yours Delors” in response to his attempts to promote further European integration and a single currency for the EC, and labelling Delors “the Froggie Common Market chief”.

I need hardly say that the English, especially, are super sentimental and place a lot of stock in their institutions. I happened to be there when the switch was made to decimal coinage and the controversy exists to this day, especially as to the names of the new coins.

When there was first a threat to the pound — and it was a real one — and then to the Royal family, probably not so real, the backs of many English were up. My thought when Prime Minister Cameron announced the referendum was that the “toffs” and others would not deal with the real issues on voters minds. This referendum wasn’t being held in the clubs of Pall Mall or on the verandah at Lords but in the public houses all over the land. Dealing just with England, where the majority for Brexit sprang, what were the issues of that time?

Freedom of Movement

Certainly the breakdown in relations between Germany and France, with Germany one more time becoming the dominant nation in Europe, was very disturbing. This went right to the guts of the matter for wasn’t this new relationship the basis of peace forevermore?

There was also rising resentment at further loss of sovereignty to the EU, the question of the pound lingered and the English particularly did not want to give up their pound for the Euro, however irrational or economically inconvenient that stubbornness might prove.

But the elephant in the room was the Freedom of Movement principle, in operation since the creation of the European Economic Community and primarily designed to support the economies of EU countries by providing a mobile work force. Never wildly popular, the massive refugee situation made this into a problem that not all the “liberals” in the U.K. could explain away.

I don’t mean to suggest that there weren’t many more issues than these because of course there were but the folks holding a glass of good old English bitter saw their security threatened, more and more loss of sovereignty and Britishness, and hordes of unwelcome tawny Muslims swamping their “scepter’d isle”.

That’s the great weakness of popular democracy — the guy in the pub gets to vote too and might just not agree with his betters.

Canada not big on democracy

Canada has never cared for democracy much. It certainly wasn’t what the Fathers of Confederation had in mind when they made sure that the elite wouldn’t have the last say with the Senate. It seemed such a good idea to ensure that regions with smaller populations would have some clout at the centre but good ideas can be carried too far when left to work like they’re supposed to.

The solution was to make sure that Ontario and Quebec always ran things, that only the wealthy were eligible and then, just to make absolutely sure, the Senators for each province were appointed by the Federal government. All serious attempts to change this anomaly have been strangled at birth.

Voters surprise PMs

There have been referenda, notably on Conscription in 1942 and the Charlottetown Accord referendum in 1992.

Neither worked out quite like those in charge wanted.

Mackenzie King’s vote on conscription managed to further aggravate French-English relations, which have not fully recovered yet. The Charlottetown Accord was, in my opinion, a huge success for the people but shattered Prime Minister Mulroney’s political career, that of his successor, and, for some years, his political party. There has been no appetite amongst the chattering classes for any more referenda.

On the other hand, I would argue that Charlottetown whetted the appetite of the public for a direct whack at the PM from time to time, but this notion has been ignored by the elite, even though there has been an ever increasing grumble amongst the people that they’re not satisfied with the present system of governance.

Treehuggers go from villain to hero

Don’t stretch from this that government by “initiative” is just around the corner. What’s happened is a slow but steady build up of resentment against the institutions and people set in authority. The establishment, political and economic, has chosen to pretend it’s not there. Yet, whereas not too long ago environmentalism was seen as a left-wing issue exclusively, if anything, they’ve been left behind in the struggle to preserve what we have rather than destroy. This isn’t a matter of changing fashions but a combination of issues amounting to a true renaissance.

People began to see that there was more to life than a new bridge or a bigger skyscraper. They watched inexhaustible supplies being rapidly exhausted. It became clear that both industry and government, and often unions as well, were not only being economical with the truth but lying through their teeth. What was absolutely essential wasn’t essential at all, unless making a bunch of money was the object.

Oceans and lakes and wild animals took on a new meaning. Treehuggers, once condemned by the decent sort of person, found themselves supported by the majority who, unlike the developer and the government, could see limits to the number of valleys and trees to be exploited. When oceans no longer teemed with sea life but plastic bottles and toilet paper, alarms slowly but steadily spread and continue to this day. This brings us, in a strange way, to Brexit.

Justin can’t have his cake and eat it too

Glamour doesn’t last anymore and the public simply won’t accept Justin Trudeau, the hero of the environment, in Paris and Justin Trudeau the man frantically trying to build more LNG plants, pipelines and expand use of fossil fuels. There was a time when that sort of hypocrisy was expected, but times have changed and Mr. Trudeau and leaders like him all over the world are waiting for another large shoe to drop.

How is it possible, ordinary folks ask, we have the world’s worst polluter, the tar sands, yet after all the lofty pledges at Paris, are moving to develop them as quickly as possible. How is it possible to square that circle?

Of course the Liberal party has found that you can do this if you’re not bothered by hypocrisy. They never have been. A very good example occurred in my area of Howe Sound where the Trudeau government had scarcely taken over before they approved Woodfibre LNG in Squamish on a shocking environmental assessment then held a seminar through their local MP to teach us why climate change was bad and how to avoid it!

Collision course

The public is no longer fooled and, as the warnings of science increase exponentially, combined with an unwillingness to accept a word as told by developer or government, the collision comes closer.

As with the EU, the elite find it best not to listen, or think they hear things they don’t. It came as a huge shock to London to learn how so many Brits were angry at issues thought to be dead. The “higher purpose persons,” in the late Denny Boyd’s marvelous phrase, assumed that issues most important to them led everyone else’s list too.

The obvious solution is not to hold referenda where Jack’s as good as his Master, but rely upon “good old parliament” to go through democratic motions and make sure that, as always, the Golden Rule applies and that those who have the gold rule.

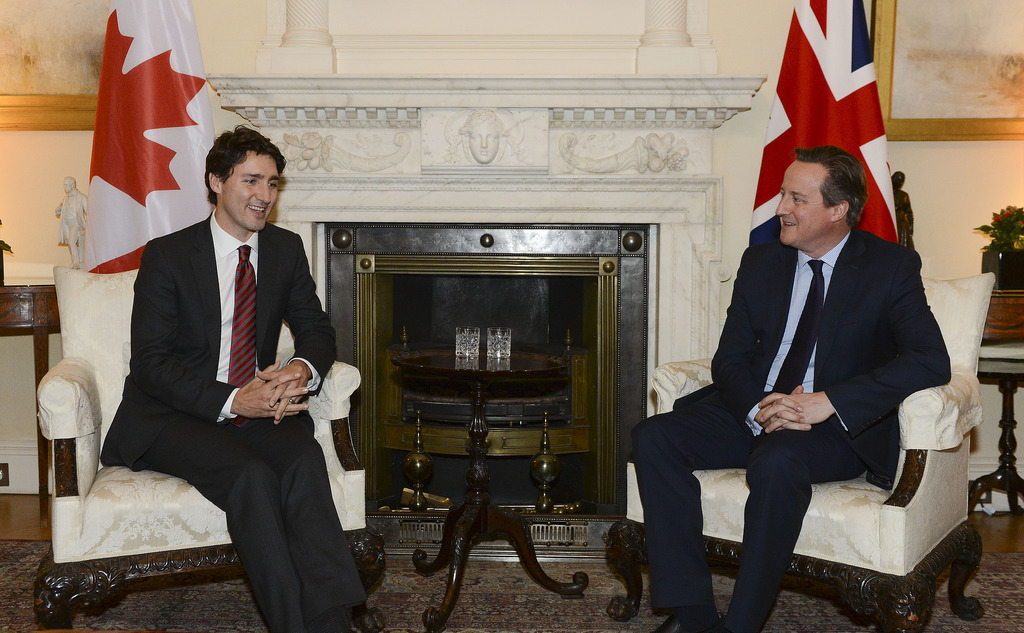

But what if this silly notion of real democracy prevails and Trudeau, like David Cameron, finds he must consult the public directly.

One thing is sure — the elite won’t have any idea of what the public is really thinking, the pollsters will ask all the wrong questions, and the “rabble” will rise.

Brexit really did happen, was not confined to Britain and is a very long way indeed from being a spent force.

This article was originally published in the Common Sense Canadian.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: Flickr/Number 10 Credit: Georgina Coupe