There were some grim remembrances last week for those dwindling few of us who consider the past travails of unions and workers worth preserving as part of our collective heritage. Their struggles and tragedies are as dramatic as history gets. Yet they claim very little place in what students are taught about the province’s history.

We are getting better at changing history from just what dead white guys did long ago, even if we de-emphasize these events a little too much in our schools. They did shape this country, after all, and we should know about them. While John A. Macdonald, for instance, did some bad things (Louis Riel, treatment of First Nations, etc.), without his vision, strength of character and political acumen, parts of Canada might long ago have been swallowed up by you-know-who south of us. Sadly, few students seem to know much about Canada’s first prime minister, warts and all.

Still, Aboriginal history and the deadly travesties we inflicted upon our Indigenous people, along with past racism against ethnic Chinese, Japanese and South Asians are now part of the school curriculum, and that’s a good thing. “Teaching students about past discrimination minority groups faced in this province…encourages [students] to value diversity, care for each other and stand up for the rights of others and themselves,” an education ministry official explained, as B.C. announced the history of residential schools would be taught, too. But why does that laudable sentiment not include the decades-long fight of ordinary workers for a decent working wage, a safe workplace and the basic right to join a union, plus the discrimination they faced every step along the way?

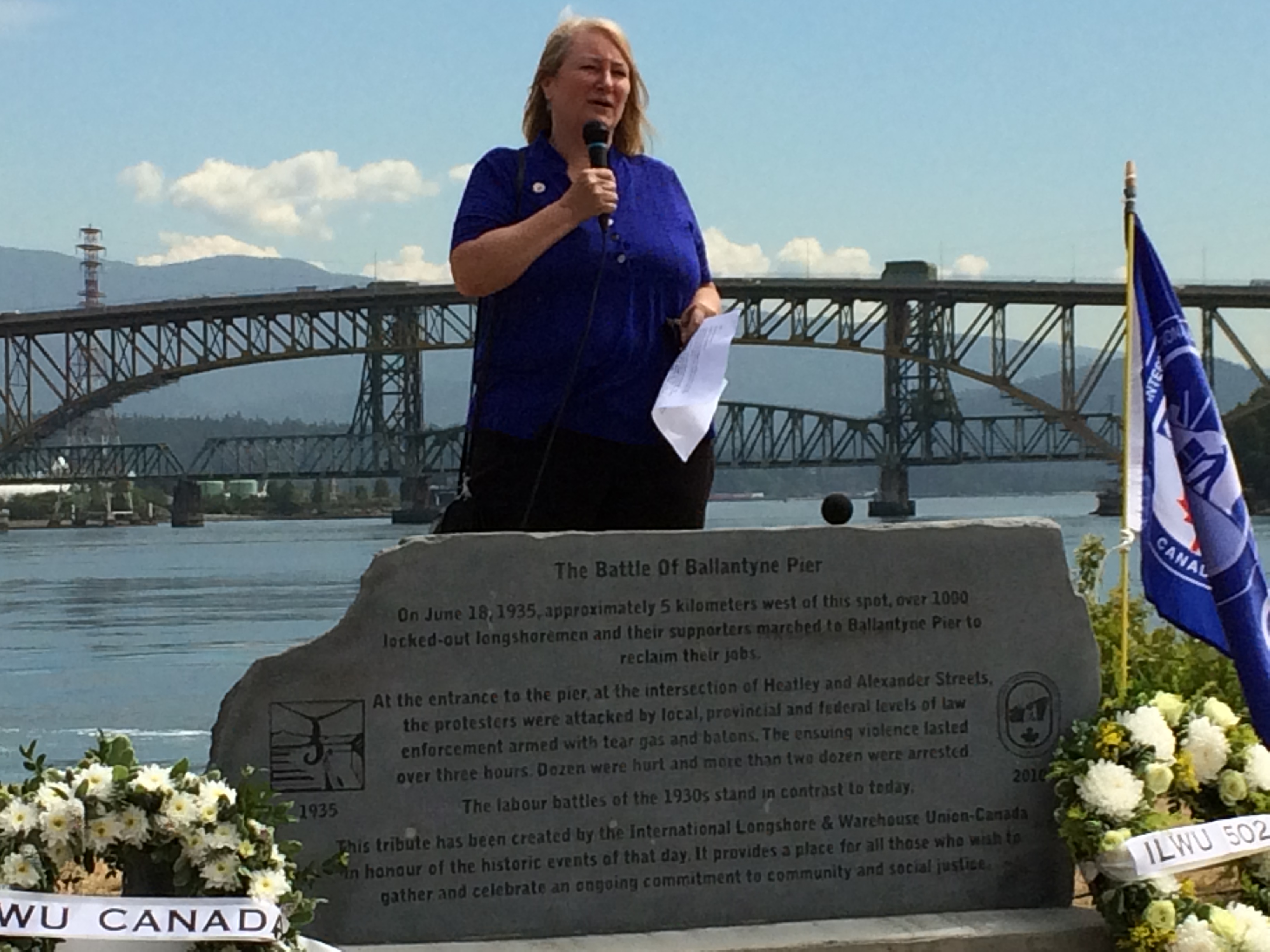

I was thinking about this, as I attended a ceremony last Thursday marking the 80th anniversary of what’s come to be known as The Battle of Ballantyne Pier, although much of it — not all — consisted more of workers getting their heads busted by police than any real “battle”. The event was held at a commemorative cairn on the shores of New Brighton Park in East Vancouver, where the city’s working port was in full hum. I couldn’t help but notice as well the imposing structure of the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge looming behind the speakers. The day before was the 57th anniversary of the god-awful collapse of that bridge, then known as Second Narrows, which had been under construction across Burrard Inlet. Nineteen workers perished. Both the Battle of Ballantyne Pier and the Second Narrows Bridge disaster are unprecedented, black days in the history of working people in this city. Yet, except by some individual teachers, they are ignored in our classrooms.

Here’s a bit about each. See if you don’t think they are worthy of learning about.

In early June, 1935, longshoremen on the Vancouver waterfront hit the bricks to support their brothers in Powell River, where a non-union crew had been used to load a cargo ship. They were inspired by the recent, historic strike in the United States. Dock workers up and down the Pacific Coast spent 83 days on the picket line, at the cost of six lives, for union recognition. Imagine, six workers died, gunned down by company thugs, just for wanting to belong to a union. You won’t find that in American schoolbooks, either. Led by the legendary Harry Bridges, the West Coast longshoremen won their strike. For the first time, there would be a union hiring hall, with dispatchers elected by the workers.

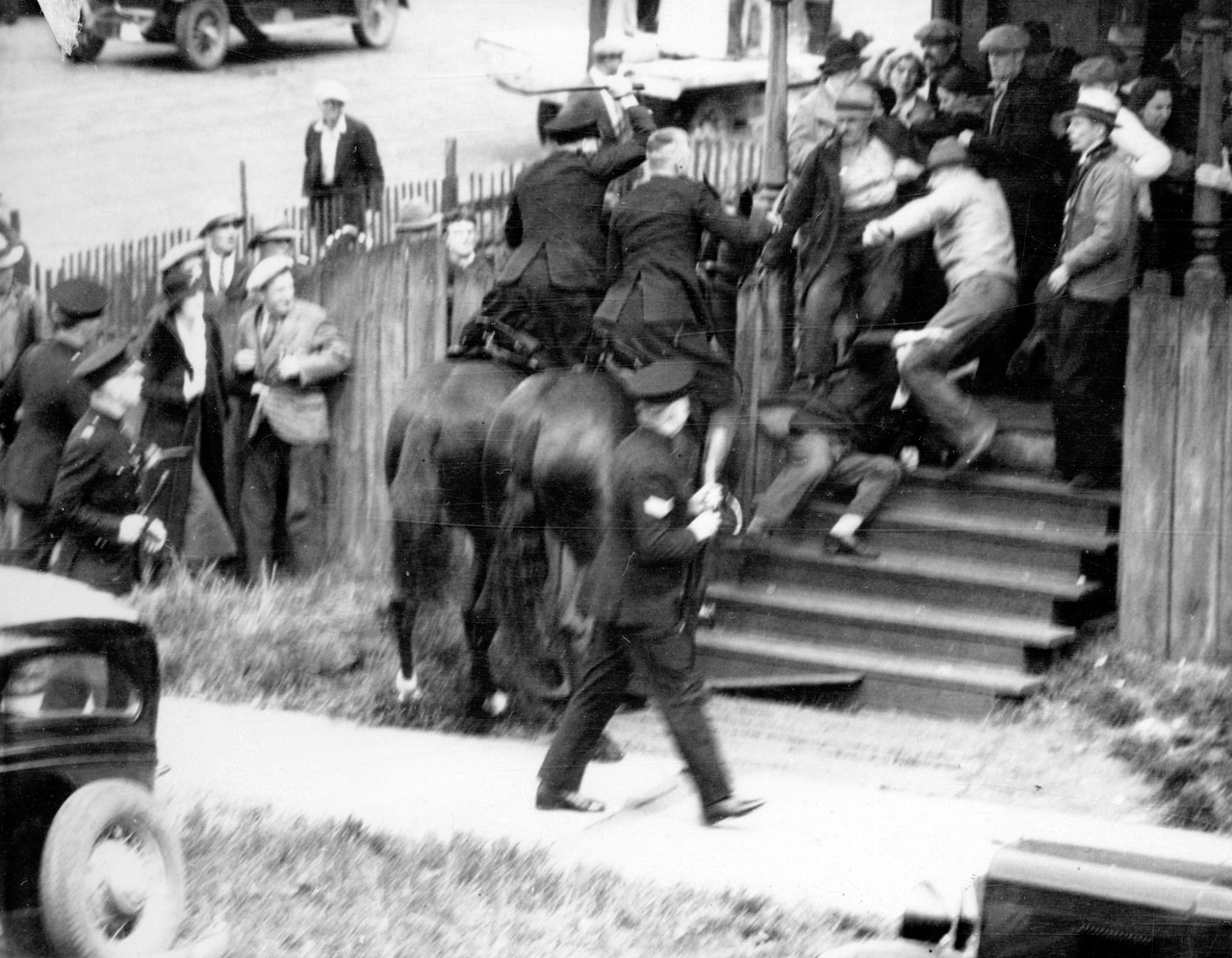

The walkout in Vancouver also became a fight for a real union and fair hiring. Fearful of what had happened in the States, however, local employers and authorities were determined not to give in. On June 18, Victoria Cross winner Mickey O’Rourke led a march of 1,000 longshoremen and their supporters towards the docks. The intended to “talk” to strikebreakers brought in by the maritime companies. A mass of police waited for them, billy clubs at the ready. Many were on horseback. At the bottom of Heatley Avenue, the men refused police orders to disperse, and the carnage was on.

For the first time, tear gas was unleashed in Vancouver. The strikers quickly scattered. But that wasn’t enough. The police pursued them with a vengeance, bashing heads as they advanced. There are amazing photos from the day, showing horses charging up the street after fleeing protestors. One famous shots shows two police officers on horseback going right up to the steps of a house, clubbing defenceless workers as they tried to take refuge on the porch.

Wherever they discovered a group of union men, even inside residences and buildings, police shot off more tear gas. It was as if they had a new toy. Some marchers fought back, hurling rocks, and one cop was beaten, after being dragged from his car. But the strikers bore the brunt of the violence. By the time the most pitched confrontation in Vancouver history ended four hours later, the streets of Strathcona were stained by blood. Sixteen police and 12 citizens, not all of them protestors, were treated in hospital, including an elderly woman shopper who was clubbed after refusing to get off the sidewalk. Up to a hundred marchers were injured and treated at hastily organized, makeshift first aid centres. Scores were arrested, and many sent to jail.

The walkout continued late into the fall, but unlike the great union victory in the United States, this one ended in defeat. Hundreds of those who took part were blacklisted, never to work on the docks again. But I suppose this sort of discrimination and battle for basic rights is not yet ready for our province’s school curriculum. Local historian Janet Nichol has just written an absorbing account of what happened that day in and around Ballantyne Pier.

Meanwhile, a day earlier, a small group had gathered on the noisy Ironworkers Memorial Bridge to mark the anniversary of Vancouver’s worst-ever industrial accident. Known for years as the Second Narrows Bridge, the Burrard Inlet crossing was renamed in 1994 to commemorate what happened midway through its construction. Just before quitting time on June 17, 1958, there was a loud, terrible crack. One span collapsed, taking another span with it. Seventy-nine men plunged from their lofty perches into the cold, swirling waters below, amid a deadly torrent of steel and concrete. Eighteen workers lost their lives, 14 of them union ironworkers. Several died standing up on the sandy bottom, anchored by their heavy tool belts. The nineteenth victim was a diver, who was killed in the underwater search for bodies.Tales from the disaster are as blood-curdling and heroic as anything you might read about the Plains of Abraham. Among the heroes was a fledgling, 16-year old diver named Phil Nuytten, who went on to international fame in the world of submersibles and diving suits. This is what I wrote on the 50th anniversary of the collapse forThe Globe and Mail.

Stompin’ Tom Connors wrote a song about it. So did American country star, Jimmy Dean. Gary Geddes has written Falsework, an entire book of poems about the tragedy, and Eric Jamieson has authored The Tragedy at Second Narrows, a fine book about what happened and the mystery surrounding the fatal mathematical miscalculation that brought the spans crashing down.

There is also a good short video on the collapse by the Labour Heritage Centre, which is doing an excellent job preparing material for those teachers who want to present some labour history to their students.

But mostly, this tragic reminder of the price working people sometimes pay just for going to work isn’t taught in our schools. One wonders why.