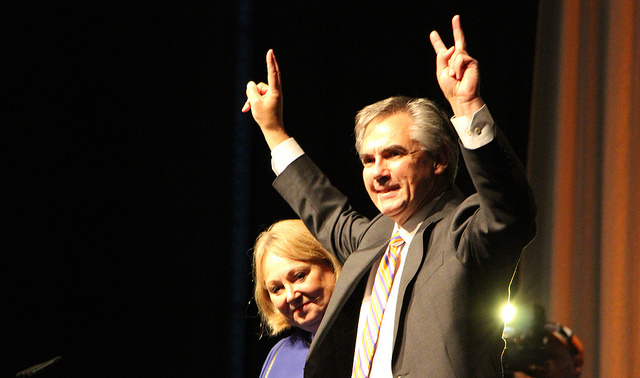

“Tonight, we begin the work of advancing and protecting sound, conservative fiscal principles.” — Future Premier Jim Prentice, victory speech, Sept 6, 2014

It hasn’t escaped Ms. Soapbox’s notice that the party that bills itself as fiscally conservative has us on track for a $20 billion infrastructure debt — at a time when Alberta’s economy is booming. Heaven help us when the economy tanks.

Mr. Prentice promised on a stack of political bibles to build 90 new schools (40 more than Redford promised) and renovate 70 more. He’ll repair hospitals that were cited for health violations (and yes, Mr. Drysdale, this is an infrastructure problem and yes, you are the minister of mice) and cap the infrastructure debt, estimated to be $20 billion, without touching the 10 per cent flat tax or existing royalty structure.

How is he going to do it?

Easy. He’s going to rely on P3s and P4s.

Public-private parternships

Public-private-partnerships (P3s) are an alternative to the traditional way that government builds infrastructure.

Under the traditional model, the government designs an infrastructure project, finances it and puts it out to tender. A contractor builds it and someone else operates and maintains it. Cost overruns or performance problems are the government’s responsibility because it created the design in the first place.

Under the P3 model, the government shifts the financing, design, construction, operation and maintenance of a project to the contractor. In theory the contractor bears the risk of interest rate fluctuations, schedule slippage, cost overruns and operational problems. It is assumed that the contractor will be more efficient than the government and the overall cost of a project will be lower than under the traditional model.

As we discovered with cold-fusion, theory does not always reflect reality.

Cheaper and more efficient?

A contractor’s cost of borrowing is always significantly higher than the government’s because banks know that governments don’t go belly up whereas contractors do (with alarming frequency). A loan to a contractor is more risky. The risk is reflected in the interest rate and the contractor passes this extra cost on to the government.

The contractor also expects to make a healthy profit and builds his profit margin into the overall cost of the project.

Regardless of how carefully the lawyers draft the P3 contract to make cost overruns, schedule slippage or performance problems the responsibility of the contractor, the minute these problems arise the contractor balks. Both sides threaten litigation while at the same time trying to negotiate a resolution — which invariably boosts the government’s costs. (Ms. Soapbox is a lawyer; she’s worked on countless EPC contracts and knows this from personal experience.)

The U.K. experience

P3s have been used in the U.K. since 1992. Allyson Pollock, one of Britain’s leading authorities on public private partnerships, says they’re an unmitigated disaster.

She reports that 159 hospitals, prisons, schools and roads were developed using the P3 model (called PFIs in the U.K.). The debt for the hospitals alone is $30.6 billion.

Instead of repaying the debt at the government interest rate of 1.5 to 2 per cent, the public is burdened with a private sector interest rate of 10 per cent to 20 per cent over 30 to 60 years, plus the additional cost of delivering a profit stream to the contractors’ shareholders.

P3s have been the subject of numerous U.K. Parliamentary Committees.

Andrew Tyrie MP, Chairman of the Treasury Select Committee says “[P3s] means getting something now and paying later. Any Whitehall department could be excused for becoming addicted to that”. He concludes “We can’t carry on…expecting the next generation of taxpayers to pick up the tab. [P3s] should only be used where we can show clear benefits to the taxpayer.”

Returning to Ms. Pollock’s hospital example, under the traditional model hospitals paid five per cent of income to service debt, but under the P3 model they pay 30 per cent of revenue to service debt. The result is a reduction in staff and quality of service and the acceleration of the privatization of healthcare — hardly a clear benefit anyone but the private sector.

Value for money

The Wildrose party agrees that financing is an issue and would use P3s for everything except project financing which would remain a government responsibility.

This sounds reasonable at first blush, but it undermines the integrity of the Value for Money analysis used by fiscally prudent governments to decide whether to build infrastructure using the traditional model or P3s.

The Value for Money analysis compares total project costs (capital, financing, retained risks and ancillary costs) for a project under the traditional method and the P3 method.

While I’m not an economist (thank god) even I can see that pulling the financing component out of the Value for Money formula is a non-starter because it makes it impossible to assess the contractor’s risk of bankruptcy, thereby increasing the government’s risk of failure.

Furthermore the Wildrose solution does nothing to address the fact that P3s divert taxpayer dollars into the contractors’ shareholders’ pockets.

P4s?

Apparently even the rampant use of P3s isn’t enough to cover the infrastructure budget. So the PC government is moving to P4s.

P4 are public-private-partnerships plus philanthropy. Well-heeled Albertans are repeatedly tapped to contribute philanthropic dollars to various government infrastructure projects; the $50 million infusion to the Alberta Children’s Hospital is a prime example.

Altruism is a good thing, but when the people of Alberta have to rely on charity for fundamental infrastructure something is terribly wrong.

Gordon Gekko and Blanche DuBois

It’s time for our “fiscally prudent” government to explain how it intends to fund the promises that put Mr. Prentice into the premier’s office. Relying on P3s which simply hide the debt and enrich the private sector (hello Gordon Gekko) and P4s which throw us onto the kindness of strangers (hello Blanche DuBois) just don’t cut it anymore.

Image: Flickr/Dave Cournoyer