A recently released volume from Creekstone Press, The Enpipe Line, presents a poetic manifestation of resistance. Written in opposition to Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipelines and similar projects around the world, the collected works resonate as series of insurgent gestures. The collection projects a wave of words intended to surround, submerge and suffocate the pipelines.

The Enbridge Northern Gateway project proposes the construction of 1,170 kilometre twin pipelines to carry bitumen from the Alberta tar sands to port at Kitimat. A thick, sticky form of crude oil, bitumen is so heavy and viscous that it will not flow unless diluted. Enbridge proposes using one 20 inch diameter pipeline to ship natural gas condensate east in order to thin tar sands bitumen for transport. Diluted bitumen would then flow west along the larger 36 inch diameter pipeline at a rate of 525 thousand barrels per day. At the port in Kitimat, the heavy crude would subsequently be loaded onto supertankers for export, filling approximately 225 tankers per year.

Faced with the numbing scale of this proposal, there are moments when capacity for words seems almost entirely surpassed. What can words do to counter the overwhelming force of a $5.5 billion industrial project? How can the weight of words block the flow of thousands of barrels? How can the strength of a poem slow the progress of a tanker?

The federal government has been unequivocal about the importance of this pipeline to their economic strategy. Traditionally, crude oil has flowed south to American markets. The Canadian Minister of Natural Resources, Joe Oliver, has not minced words about the “need to diversify our markets in order to create jobs and economic growth for Canadians across this country.”

But the economic clout of the oil industry is not the only thing that matters in the debate around the Enbridge pipeline. Millions of living organisms depend on the environments threatened by this development. The pipelines would cross more than 700 streams and rivers, and risk contaminating major salmon-bearing watersheds with a spill. The introduction of supertankers to the North Coast of British Columbia, in some of the world’s most dangerous waters, would bring further risks to fragile coastal ecosystems. Perhaps most significantly this pipeline expansion would create the capacity for an estimated 30 per cent increase in the development of the Alberta tar sands, an almost unparalleled global climatic catastrophe.

The assembled poems within the pages of The Enpipe Line witness the profound ignorance guiding the unfettered pursuit of wealth, and respond with a profession of devotion to the dream of a better, sustainable world. Reading these poems, I was reminded of the motto of Bertolt Brecht, who wrote during some of the darkest times of the last century at the height of fascism. “In the dark times / Will there also be singing? / Yes, there will also be singing / About the dark times.” While poetry may seem an indulgence in our own dark times, it remains an absolute necessary.

Potent words denaturalize the myths of progress. In her poem, “Say,” Melissa Sawatsky rebuts the presumptions of reigning industrial designs. “The land / doesn’t want your pipes for veins, / doesn’t need the petroleum/condensate / exchange.” Jordan Hall’s poem, “Sub Rosa,” similarly exposes the industrial arrogance of development.

The earth does not want to surrender its bones

But we have better uses for them

thank to lie in the ground

we’ll amputate mountaintops

transect, vivisect

shake the foundations

each successful surgery a monument

to our ingenuity, capability

This verses powerfully reposition civilization’s technological achievements as violations of the body of the earth. These poets speak back to authorized narrations of corporate plans and government reviews. Figuring technological interventions as invasions into the corporeality of the planet, these writers articulate counter-stories of the land. These poetic interventions connect to broader struggles for the land, dislocating the hold of dominant narratives and opening spaces of contestation.

Poets also continue to remind us of those very things which dark times threaten to crush into irrelevance. In her poem, “Shooting the Moon,” Alex Cuff poignantly reminds readers of both the grandeur and beauty of our world.

Michael Collins, the unlucky bastard who didn’t walk on the moon

says the best thing about looking

at earth from space

is how beautiful it is.

Elsewhere, on land overlooked by NASA,

a stream passes freely over mossy rocks

A river line through roots of beech tree and young oak.

Thus, Cuff articulates the value invested in the natural environment both as a global entity and localized ecosystem.

Inhabiting the riparian landscape, Marilyn Belak’s “The Fishing Poem” recounts both her exceptional and quotidian experience of “catching the trophy fish.” Immersing the record catch in the activities of “that long day / I spent on the shale bank beside the road on the Tahltan river,” Belak describes the pattern of the day “when my son was one / and napped all day while I watched.” She contextualizes her experience on the river, “when there was nowhere to walk but away / from my sleeping child or towards the bears,” thus embedding her struggle with the big fish within her responsibilities as a mother left to care for camp. She remembers the epic character of her struggle with the big fish: “when the rod snapped / I wrapped the line over and over / my right hand and braced / my feet behind a boulder / got sprayed when he rose so close / to shore he flew over my head.” And celebrates how she was the toast of evening, in “the good dress I had packed / for Vancouver,” having bested the men who left to spend the day fishing.

Through such interventions, contributors refuse to abandon aesthetic concerns or personal interests to the demands of politics. Instead they articulate the aesthetic and the personal as a challenge to a prevailing political-economic calculus that would neglect the value of these environments and experiences. Within the context of a struggle against environmental devastation, these poets articulate the necessity of maintaining beauty and joy in the world.

Writing of the value of living community, contributors dream of the potential to fix a broken system. Christine Leclerc muses: “Has anyone developed an algorithm / that depicts the ways in which the boom and bust cycle / maps to the conditions that shove / us down until energies bubble up, burst / and negate corruption?” While such a formula remains elusive, the cultural politics that constellate particular narratives of value undoubtedly constitute a key term in this determination.

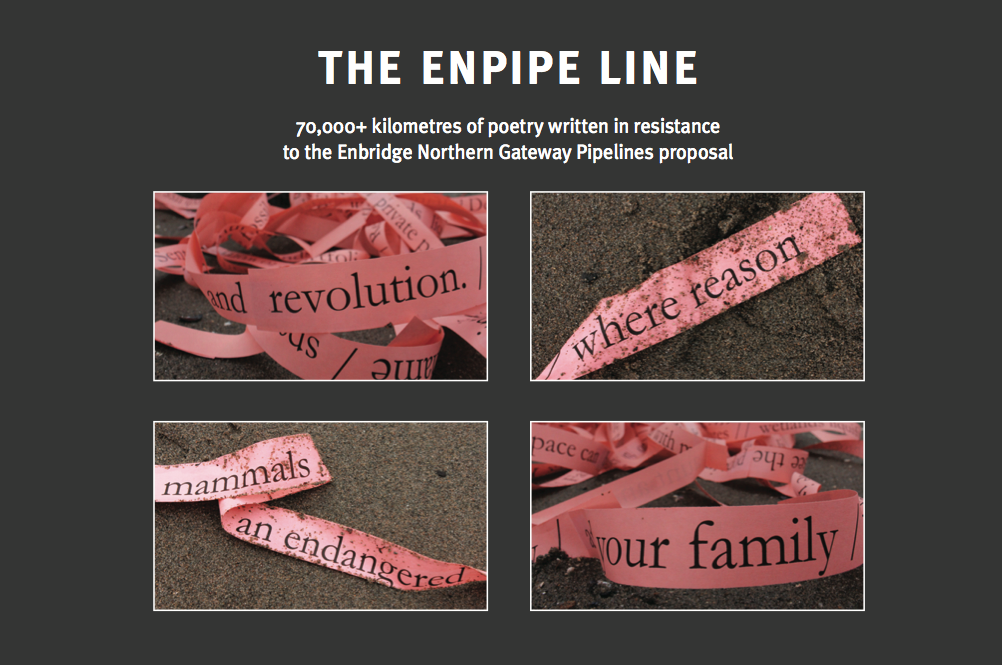

In questioning dominant value chains, and forwarding the salience of other considerations, the poets collected together in The Enpipe Line challenge prevailing visions of pipeline development. Mercedes Eng’s poem, “In My Dreams,” speaks directly to her political aspirations and resonates with the broader impetus of the collection: “i write poems all over your pipelines / directing the oil back to the ground.” Encasing the Enbridge pipelines in words, these poets help construct the foundation to block the narrative of pipeline development, and contribute to the vital task of finally shutting the pipelines down.—Tyler McCreary

Tyler McCreary is an Indigenous solidarity activist based in northern British Columbia and a regular rabble.ca blogger.

You can listen to audio from The Enpipe Line book launch, which was held in front of Enbridge’s offices on Burrard Street in Vancouver.