Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

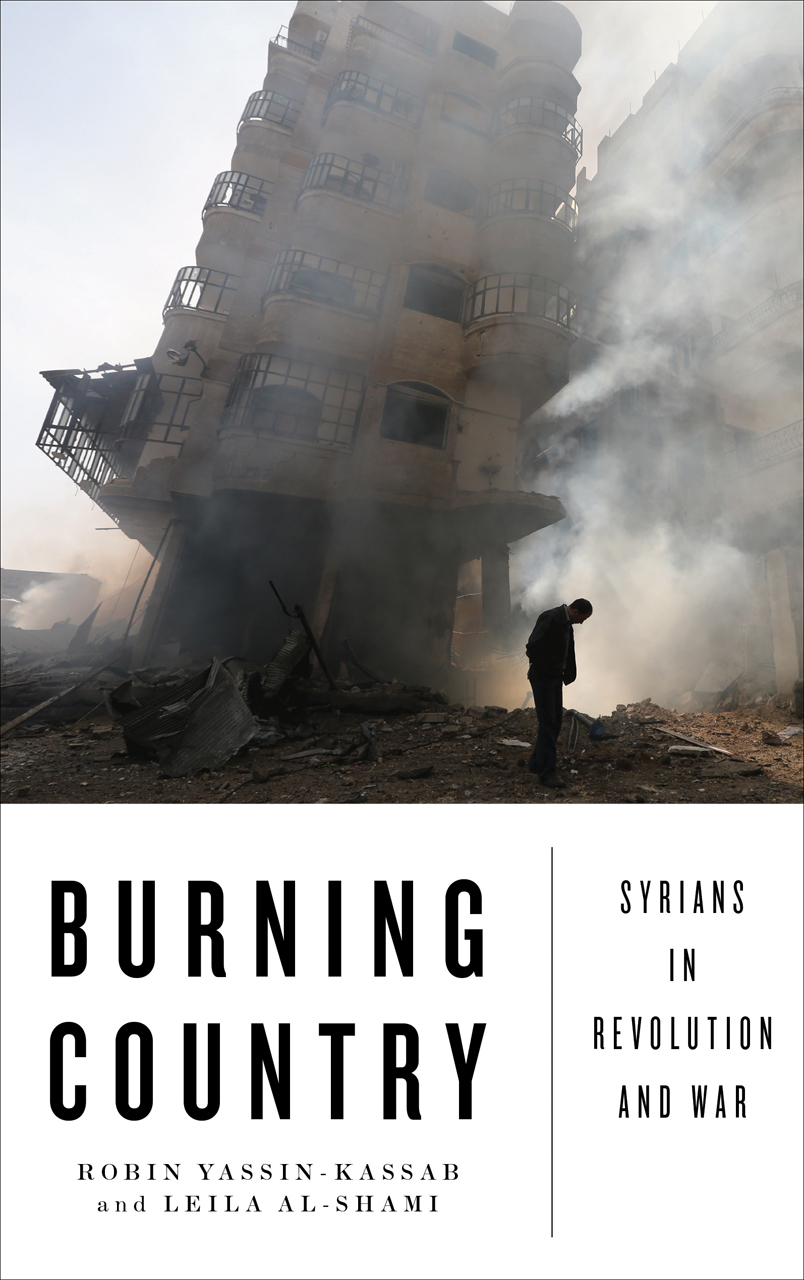

No recent conflict is as misunderstood as the Syrian Revolution asserts Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War authors Leila Al-Shami and Robin Yassin-Kassab. They make the case that the conflict should be seen as a revolution, despite its complexity.

Al-Shami and Yassin-Kassab start with some much needed historical and political context. We learn that the image of the Assad regime being secular, anti-sectarian, and pro-women to be a myth sold to the West to make the regime look acceptable compared to the Islamist alternative. Women have never had legal equality. Christian or Islamic law is used instead of a civil code for family law.

This is badly needed context, as reports on the conflict tend to begin with the mass anti-Assad protests in 2011.

This carefully cultivated image that the regime has generated for Western eyes versus the reality on the ground also extends to the Syrian Revolution itself.

From the first peaceful protests in 2011, President Bashar al-Assad has tried to paint the opposition as sectarian extremists willing to resort to violence. Assad has also been happy to portray all oppositionists as Jihadists to scare the West. He released many Jihadist prisoners from Syrian prisons. Assad’s gambit in releasing Jihadis has paid off, with many Western observers giving up the notion there is any sort of progressive opposition in Syria.

From the beginning of the mass protests in 2011, there has been important grassroots organizing long gone unnoticed. This is something that gets lost in all the talk of Jihadist groups and foreign intervention. It is this contrast of both daring activism and brutal violence that makes Burning Country both an inspiring and maddening read.

The most important contribution of Burning Country is the coverage of these grassroots movements for democracy before and after 2011. The authors have provided many quotes from Syrians who have been on the ground activists. Many of these activists first developed their organizing skills when Bashar al-Assad first assumed the Presidency in 2000 and there was a brief period of liberalization.

As the revolution gets underway, we learn about the vital role local councils play in the uprising. The Local Coordination Committees (LCCs) are elected, and attempt to provide local services like water, electricity, waste disposal, and even education. Though the structure and functions of LCCs vary in each locality, they offer a vision of a democratic Syria.

When the revolution becomes militarized after the regime’s violent crack down of protests, LCCs differ in their orientation towards armed groups. Many do not formally back armed opposition groups. LCCs often monitor the behaviour of armed opposition groups to try to make sure they do not behave in an authoritarian manner.

While LCCs are a sign that the conflict is more than the media portrays and something that demonstrates that Syria could have a democratic future, it’s not hard for a reader to raise certain questions.

LCCs are an example of revolutionary democracy, but are their decentralized structures ever going to be enough against a centralized state with a brutal military and security apparatus? Against a state that has fostered a Jihadist reaction? It’s a question that will only be answered in the future.

The revolutionary transformations in Syria go beyond the LCCs. There has been a “cultural revolution from the bottom up,” as the authors put it. This manifested itself in songs, art, and films. For the first time Syrians have been able to freely express themselves in opposition-held areas.

In opposition-controlled areas gender roles have been transformed. This requires women to take on other roles they have not traditionally performed. Women have been at the forefront of protests and aid delivery. These rapidly shifting gender roles invoke Frantz Fanon’s observations of how the Algerian Revolution changed gender roles in that country.

These stories of cultural expression and shifting gender roles that the authors highlight contribute to the feeling that despite all the bombs, the Syrian Revolution is a dynamic process that will last long after agreements to end the fighting have been signed.

It is also important to note how the authors deal with the issue of Islam and the revolution. The authors make clear that in a conflict like Syria’s, many turn to religion. All those who invoke Islam, despite the propaganda of the regime, do not wish to impose Sharia law or a Caliphate. ISIS’ ability to gain a foothold in Syria is also blamed on the sheer brutality of the Assad regime.

Putting Islam in its context within the conflict is an important contribution, it is something that often only gets mentioned at the same time as ISIS or al-Qaeda in the media.

The final chapter deals with an important issue that we in the West need to grapple with — solidarity. The authors are rightly critical of how Syria is seen in the West. They wish to move beyond certain negative tropes.

First, that the Syrian conflict is only Assad versus Jihadists. There are brutal and sectarian Jihadist groups beyond just ISIS operating in Syria, but the regime carries a lot of responsibility for their rise. Portraying everyone but the regime as Jihadists contributes to Islamophobia, especially towards refugees.

Second is this idea of Western-backed regime change. The authors are rightly critical of Western leftists who view this conflict like it was Iraq in 2003. The Assad regime’s historical relations with the West have not always been negative.

Until the beginning of the uprising in 2011, Assad was still seen in the West as a reformer. Combined with Assad’s neoliberal reforms, it’s surprising why many Leftists in the West choose to support him or downplay the role of revolutionaries on the ground.

The authors also provide examples of the West’s half-hearted attempts to arm the opposition in a manner that would hardly allow it to topple Assad.

As the authors point out, Syrians who have been trained by the U.S. to fight ISIS are viewed with suspicion by opposition activists who feel they have become co-opted. Focusing only on Western actions is dogmatic thinking that erases Syrians participating in the revolution of their agency.

There is much to reflect on after reading Burning Country. There are questions of revolutionary organization, how to offer solidarity, and reassessing our own views of the conflict. This book should be read by all seeking to get a better picture of what is going on in the streets of Syria without propaganda from the regime, the U.S. or Russia.

Regardless of the outcome of the conflict, Burning Country shows us that there were many Syrians who stood up in the face of great brutality to try to build a better country.

Gerard Di Trolio is an editor for rankandfile.ca. He has written for Jacobin, Briarpatch and elsewhere, and lives in Toronto. Follow him on Twitter at @gerardditrolio.