The second-quarter GDP numbers confirm that Canada’s continuing “recovery,” such as it is, is still balancing very precariously on a knife-edge between expansion and contraction. The various sources of growth vary widely in their current momentum. The overall net balance is barely positive. And coming austerity in the public sector could very much push the balance into negative territory in coming quarters.

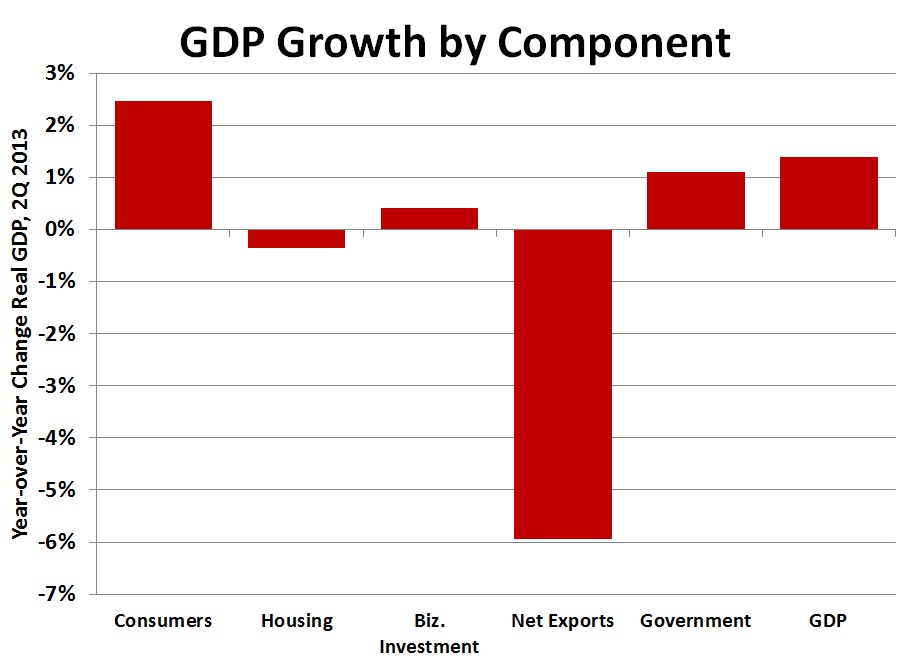

Here’s how the numbers add up. I examined the year-over-year change in each major component of GDP (the familiar C+I-G+X-M, with housing investment broken out as its own category), using real (chained 2007) data. The ultimate change in real GDP depends, obviously, on a weighted average of all the component changes. This is a simple way to think about where the impetus for growth is coming from (or not, as the case may be).

The accompanying figure summarizes the data. Consumers are still spending at a decent clip, despite (or more precisely thanks to) their accumulating debt. Residential housing investment has now peaked and is starting to decline moderately. (Recent data on housing starts and residential construction employment suggest further flatlining or gentle contraction in this volatile sector.) Business capital investment continues to be lacklustre, despite abundant corporate cash flows. In fact, this graph overestimates the strength of business investment because of well-known problems with the implicit GDP deflator for this category of spending (apparent prices of business capital are distorted downward by the secular fall in the price of computer-related assets, and this makes “real” investment spending look bigger than it is — at least in macroeconomic terms). Net exports are a wipe-out: the trade deficit continues to widen in the face of iffy global demand and our overvalued currency. This result is especially disappointing in light of recent improvements in U.S. demand conditions; it indicates the deep structural weakness in Canada’s participation in the global economy that the Harper government’s rush to sign more FTAs will only reinforce.

This leaves the government sector, considering both current “consumption” (spending on programs) and capital investment (infrastructure). The net year-over-year increase as of the second quarter was still positive, but barely so: up by 1 per cent in real terms. This reflects growth in real current consumption (up 1.4 per cent year over year), offset by a contraction in capital spending (down half a percentage point). The net trend in total government spending has recovered from the significant negative values recorded in 2011 (as temporary stimulus spending, mostly on capital “make-work” projects, was being unwound). But at barely 1 per cent real government expenditure is still shrinking both as a share of GDP and in real per capita terms, and hence can be considered evidence of continuing austerity. In contrast, when the economy was recovering much more robustly in latter 2009 and 2010, total government expenditure was growing by as much as 6 percent year over year.

The weighted average of all sectors produces the uninspiring 1.4 per cent year-over-year expansion in total GDP recorded in the second quarter. That’s not enough to offset productivity growth and population growth — which is why there has been no further recovery in the national employment rate (employment as a share of the working-age population) since the end of 2010 (almost 3 years of labour market stagnation). This isn’t so much a “recovery,” as it is treading water.

What’s the outlook going forward? In short: more of the same. There’s no sign of coming vigour in either net exports or business investment (what are supposed to be the major engines of growth in a globalized capitalist economy). Best-case scenario for the housing sector is a continued soft landing: that is, an easy-going decline. Consumers are still willing to borrow and spend, for now: how that will hold up in the face of coming interest rate hikes (on both mortgage and non-mortgage debt) is an open question.

Fiscal policy will therefore continue to determine the net balance of economic forces. If governments decide to tighten spending further, then the overall balance would shift even closer to zero (or even cross to the minus side).

This simple analysis also highlights what is required to achieve a more optimistic outlook — one where expansion in spending is sufficient to generate a sustained increase in the employment rate, with resulting spin-off benefits for incomes, spending, and subsequent job-creation. New industrial and trade policies could help to address the weakness in net exports and business capital spending. Failing that, fiscal policy must do more of the economic lifting. The corporate sector continues to deleverage and accumulate liquid assets; there is no shortage of “money” in Canada’s economy. From a social perspective, therefore, there is no fiscal constraint on government’s ability to lead future growth through a major and sustained expansion in spending (especially capital spending — for example, on transportation, housing, and green energy).

After all, that’s how we solved the last decade-long stagnation. Today, five years after Lehman Brothers, it’s increasingly clear we need something similar (hopefully not motivated by war) to end this one.