You can change the environmental conversation. Chip in to rabble’s donation drive today!

You could say Tomas Borsa and his buddies have drawn a “line in the sand” between anger and activism. Spurred by what they saw as the lack of deeper public and community input into the environmental risks of a twin pipeline that would run 1,177 kilometres between Bruderheim, Alberta to Kitimat, B.C. the gang got their game on.

The combination of the two pipelines in the Northern Gateway Pipeline project would carry an average of 743,000 barrels of crude oil a day. At issue is Enbridge’s pipeline safety record. Between 1999 and 2010, the company reported a total of 804 spills in Canada and the United States. In 2010, an Enbridge pipeline in Michigan ruptured and went unresolved for 18 hours, pouring more than 3 million litres of oil into the Kalamazoo River. According to Line in the Sand, “the incident is officially the single largest inland oil spill ever recorded.”

With a stash of tree-planting funds and a small amount raised through Kickstarter, Borsa and his four friends hit the road — gathering information, interviews and creating an interactive site called Line in the Sand.

It began in the summer of 2012 and will continue until the end of this year — culminating in a Dec. 31 deadline in which a decision by the Joint Review Panel of the National Energy Board is due. The panel, after hearings in 21 locations across Alberta and B.C., will reveal whether the pipeline has been approved. The federal cabinet will have final say on the project.

The guys will be releasing their documentary on the site soon after the decision. A book is also in the works.

“We aren’t affiliated with any institutions or organizations, all of our expenses are out-of-pocket,” Borsa explains in an email from interior B.C. “Between airfare, gas, website hosting fees, hard drives and the odd hotel, the project has cost around $8,000 to date.”

While Borsa has some experience writing for the University of Saskatchewan’s campus paper, he hasn’t had any experience putting together such a project. Two of his co-creators though, have produced a few films between them and another is a graphic designer who put together the site. Otherwise, it is an organic effort by some very impassioned activists. Here, they answer some questions put to them about the inspiration, goals and experiences behind the project.

What got you inspired to do the project on your own?

Much of the motivation for the project came from our disappointment with the rhetorical angle taken by mainstream news outlets in their reporting on the Northern Gateway. We felt that pitting economic interests against environmental interests, First Nations against non-First Nations interests, rural (Northern) against urban (Southern) interests represented a radical oversimplification of the issues. We were quite certain that a richer, more nuanced set of perspectives would likely emerge if we engaged directly with individuals living along the route (rather than casting them into broad categories) and sought to fill that gap.

We decided to go it alone so as to avoid answering to anyone, and in so doing allow the project to take whatever form it needed to. Given the visceral connection which many people feel toward the land and territories that the Northern Gateway is slated to travel through, we expected to encounter some very impassioned responses. Doing the project on our own gave us full license to include all voices shared with us, and not just a select few.

How did you find your participants?

By doing a lot of background research before hitting the road. We specifically targeted people who had not presented at the Joint Review Panel hearings, as these are the people whose voices were, for one reason or another, never allowed to be aired in a public forum. We approached everyone we could think of: welders, farmers, mechanics, fishermen, loggers, foresters, politicians, activists, artists, teachers, professors, First Nations leaders, Emergency Response personnel, and so on and so on. Some never got back to us, some stood us up, and some offered us a hot meal and a bed for the night.

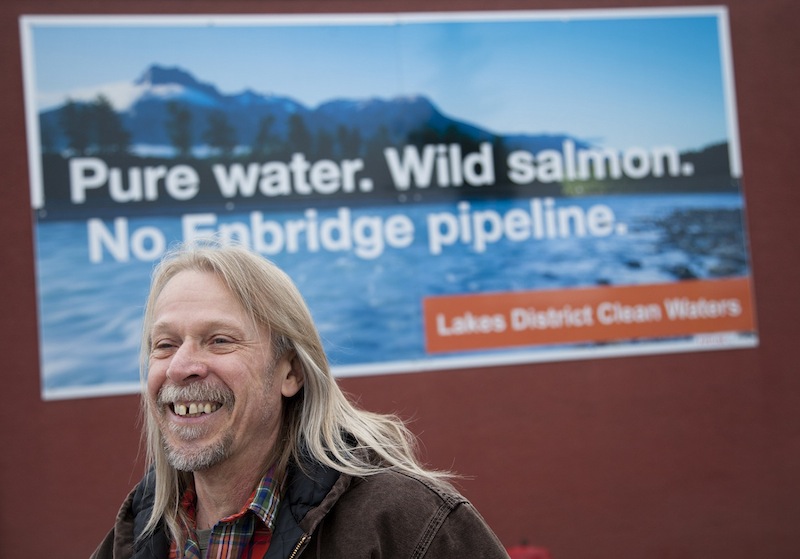

John Phair, an interviewee from Burns Lake, B.C. Photo courtesy of Line in the Sand.

One note about participants: as much of the motivation for this project was to challenge the pre-existing “us-versus-them” narrative which seemed to pervade reporting on the Northern Gateway, we deliberately reached out to as wide a group of participants as possible. Unfortunately, an overwhelming number of individuals with a pro-pipeline stance were either not interested in speaking to us, backed out at the last minute, or were unwilling to appear on camera; many also asked for us to send them “sample questions” beforehand. Thus, despite our best intentions, the unwillingness of those with a pro-pipeline stance to speak openly and on-record will be reflected in their under-representation in our documentary and book.

You could have stopped at an interactive website — why branch out to books and a documentary?

Our website allows for quick and on-the-ground summaries of the stories and people we encounter, but it doesn’t allow for much depth and analysis. Websites are a point-of-first-contact for many people, and our documentary and book pick up where it leaves off.

Our documentary allows us to show the terrain, cultures, towns and people to a much deeper degree than our website. The documentary allows us to include footage that is too lengthy, complex, or deserving of an unabridged airing to simply pare down and feature on our website.

Morice River in B.C. Photo courtesy of Line in the Sand.

Finally, the book provides us with the greatest artistic license, and can be thought of as a critically minded travelogue. Unlike our documentary, by creating a book, we are by definition re-interpreting the stories and perspectives shared with us, and are able to insert a considerable degree more self-reflection into the final product. By acknowledging our outsider status and presenting an honest summary of the perspectives shared with us, we are hoping to create a book which mounts a compelling and persuasive argument against the Northern Gateway without the need to stoop to proselytization or passive simplification.

What are the key things you’d like the audience to bring away with them?

First, that the North is not an untamed, uninhabited wilderness, and that a development of this magnitude has the potential to disrupt and affect a tremendous number of people. By focusing on the human element to the Northern Gateway, we would hope to remind our audience that these are people who should not be thought of as “out of sight, out of mind.”

Second, I would hope that our audience understand that the Northern Gateway is not simply a pipeline. Irrespective of whether one accepts its purported economic benefits, the Northern gateway is, without question, a development proposal with extreme sociocultural and economic risks. By putting at risk a wide swath of Alberta’s agricultural sector, and British Columbia’s tourism, fishing and forestry industries, the Northern Gateway could very well have negative economic impacts, both locally and provincially. Further, by putting at risk the very foundations of flourishing traditional Indigenous cultures, a spill along the Northern Gateway’s length could have disastrous effects for Canada’s First Nations.

Lastly, if our anecdotes are anything to go by… then public opinion is indeed overwhelmingly against the Northern Gateway pipeline proposal.

Like this article? Chip in to keep stories like these coming!

June Chua is a Toronto-based journalist who regularly writes about the arts for rabble.ca.

Photos courtesy of Line in the Sand.