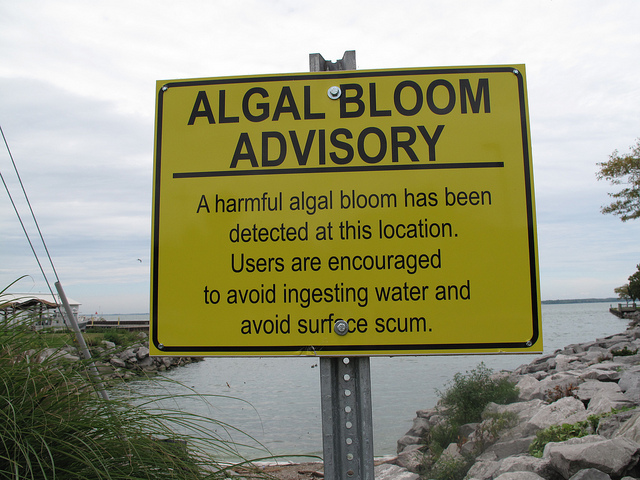

Toledo Mayor D. Michael Collins lifted the city’s drinking water ban at a Monday, August 4 news conference after three days of chaos. The National Guard had been called in to provide clean water so residents could avoid potential health effects — including skin rashes, vomiting and diarrhea — of drinking Lake Erie water contaminated with blue-green algal toxins. While some toxins remain, the mayor has declared the city’s water supply “safe” for human use.

Scientists point to excessive phosphorus as the culprit in this incident. History bears them out.

During the 1960s, laundry detergents averaged roughly 10 per cent phosphorus by weight. Lake Erie suffered massive algae blooms each summer. Whitefish, pike and walleye virtually disappeared. Research at Canada’s famed Experimental Lakes Area — now abandoned by the federal government — clearly documented the role of phosphorus. The Canada Water Act was amended in 1970 to require detergent manufacturers to reduce phosphate in detergents to 2.2 per cent by 1971. This was a key victory of the early days of the environmental movement.

In the U.S., the detergent manufacturers fought against binding national legislation. Nonetheless, citizen action led to a patchwork of municipal and state laws. Manufacturers grudgingly marketed alternative detergent formulations. This greatly reduced (but did not completely eliminate) clothes-washing as a source of phosphorus pollution. Lake Erie returned to reasonable health — for a while.

Unfortunately, phosphorus pollution and blue-green algae are back with a vengeance (e.g., in Lakes Winnipeg and Simcoe as well as Erie). Excess fertilizer nutrients from fields and pastures wash into lakes and streams and stimulate the growth of photosynthetic algae, bacteria and plants — a process known as eutrophication. High phosphorus inputs, in particular, favour blooms of blue-green algae, more properly called cyanobacteria. Toxins produced by cyanobacteria have been known for centuries to cause poisoning in animals and humans, with risks of liver and kidney damage, nerve damage, and gastrointestinal disturbances.

Phosphates in agriculture

Modern agri-business is hooked on phosphate fertilizer. Only about one-fifth of the phosphorus extracted from phosphate rock is consumed as food — the remainder is released into the environment. A large fraction of the phosphorus we consume as food eventually ends up as pollution as well. Most sewage treatment plants are not designed for phosphorus removal. This requires “tertiary treatment,” beyond the limited budgets of most municipalities.

Pollution concerns have prompted efforts to encourage more efficient phosphate fertilizer use, but it remains on an upward trend. Government subsidies for liquid ethanol transport fuels have resulted in higher corn acreage and fertilizer demand. While net environmental impacts of biofuel use are hotly debated, there is growing evidence that replacing gasoline with corn ethanol has led to greater water pollution while only slightly reducing air pollution by greenhouse gases.

This is a poor trade-off. Treating air and water pollution as separate issues no longer makes sense. We are sleep-walking into inter-connected, recurring environmental crises. More intense rainfall — a feature of our greenhouse-gas-disrupted climate — means more runoff and soil erosion and higher loads of sediment and phosphorus in lakes and streams. Streamside buffers in agricultural areas can help, but bigger changes will be needed.

The longer we remain on the fossil fuel treadmill, the faster fertilizer and food prices will increase. The fertilizer industry widely acknowledges that the quality of remaining phosphate rock is decreasing and production costs are increasing. Estimates of remaining supply range from 50 to 100 years. Within our children’s lifetimes it will be impossible to produce food (and fuel) with current agricultural practices.

Avoiding starvation will require a major shift to use of human and animal manures. This is organic farming on a broad scale — as practiced by humans for millennia. It will mean dealing with higher labour and transportation costs, appropriate application rates, risks of transmitting pathogens, and undesirable odours. Ideally, this will lead to smaller farms; mixed livestock, vegetable and grain crops; and reduction of the indirect dietary consumption of corn (used to produce meat and fructose-sweetened drinks).

Taking action to keep water safe

In eastern Ontario we are seeing hopeful signs of citizen action bringing about positive change. Cobden-area residents have formed a Muskrat Watershed Council, aimed at protecting water supplies and property values, and reducing the occurrence of blue-green algae blooms in Muskrat Lake — which has some of the highest phosphorus levels in Ontario. Volunteers with Ottawa Riverkeeper’s River Watch program are monitoring the health of local water bodies. A younger generation is getting back into farming, bringing a new environmental awareness and a commitment to healthier diets. Ottawa now has a year-round organic farmers’ market, and organic produce can be found at farmers’ markets throughout the Ottawa Valley, including in Cobden.

Despite an overall worrisome trend of increased frequency of harmful algal blooms, there are many opportunities to take action to keep water safe for drinking, swimming and fishing. One of the most important is through your pocketbook. Buy food that is grown in the most sustainable manner — not most cheaply.

Ole Hendrickson is a retired forest ecologist and a founding member of the Ottawa River Institute, a non-profit charitable organization based in the Ottawa Valley.

Photo: Ohio Sea Grant/flickr