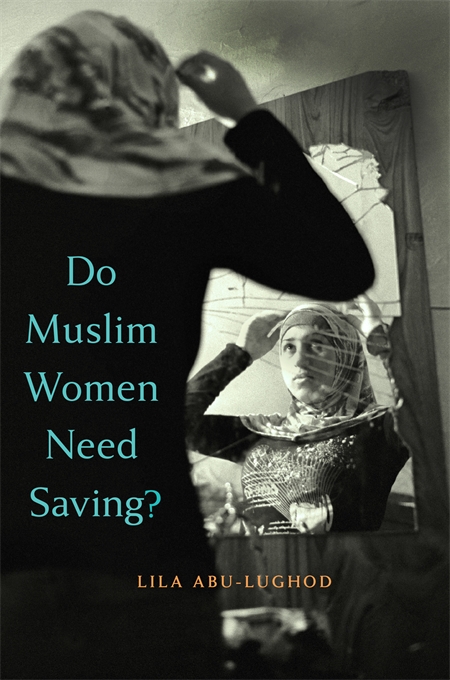

Do Muslim women need saving? This is the question author Lila Abu-Lughod tries to answer in her book published by Harvard University Press in 2013.

Abu-Lughod is a trained anthropologist from Columbia University. For several years she lived with Bedouin women in Egypt’s Western Desert. She wrote Veiled Sentiments, a book filled with poems Bedouin women tell about their men, their relationships and their lives. Abu-Lughod kept returning to visit and live with rural Egyptian women for the purposes of her studies, and one can feel throughout the book that these women are not objects of curiosity or pity, or perhaps objects of study — but rather becoming akin to close friends and almost relatives to the author. She compares her own children to theirs, speaks fondly of their attitudes, and tries so hard to understand their struggles and the dynamics of their decisions.

Abu-Lughod constantly questions herself about the reasons that would make these women look oppressed to their Western counterparts. She acknowledges that their lives are economically and socially challenging, but reports that they have never accepted their fate in any way and instead are constantly trying to change things around them at their own pace and on their own terms.

In the West, some authors and popular media make us believe that it is both the culture and/or the Muslim religion that are the causal roots of this “oppression.” But Abu-Lughod claims that her own experience actually showed her the opposite: how culture and religion can sometimes become the real engine behind the strong will of change she frequently encounters with these women.

Abu-Lughod studies in great detail the messages of “pulp nonfiction” books sold in the West, whose dangerous mixture of violence and pornographic content about the lives of Muslim women abused by their families is intended to keep the supposed link between religion and oppression alive.

Abu-Lughod exposes the pattern behind memoirs telling us horrific stories of Muslim women abused by their husbands, fathers or family, who were able to escape and embrace freedom in the West. For instance, the story of Zana Muhsen told in the book Sold is a story of a Birmingham girl who escaped from Yemen with her mother’s help after 13 years of abuse. These books are usually written by ghostwriters, sold by the millions and sometimes turned into movies. These books enter the popular imagination and become the reference points for an avid Western audience already convinced of the moral superiority of their culture and the universality of “freedom.” What Abu-Lughod names as the fantastic world of “pulp nonfiction” is filled with real or sometimes simply “invented” stories that are later used to justify moral and military crusades from the West with the dubious objective to “liberate” Muslim women from the barbarism of their culture and offer them freedom of choice.

Thus, the obsession of the Western media with “honour killing” stories does not always emerge from a genuine desire to help women fight the injustice they face in their own communities but rather from an intrinsic message that their indigenous culture is barbaric, doesn’t permit love, and forces girls to marry men they despise.

Abu-Lughod explains:

“[T]he problem is that when violence occurs in some communities, culture is blamed, in others only the individuals involved are accused or faulted. As Leti Volpp has shown in her classic article called “Blaming Culture,” violent or abusive behaviour gets attributed to culture only when it occurs in minority or alien culture, racial, or national groups.”

So what to do to improve Muslim women’s rights? Abu-Lughod gives two examples of women’s rights groups: the classical Western feminist approach and the new Islamic feminist approach. Abu-Lughod praises some aspects of both approaches but also criticizes their shortcomings. For instance, she points to the danger of the governmentalization of rights where the government would sponsor a sort of elite feminism, especially in urban centres and wouldn’t pay attention to the rest of the population in rural areas.

The emerging movement of Islamic feminism that started in Malaysia can be seen as responding to an increasing need to change the Islamic texts underlying marriage and inheritance. She cites the example of some North African countries where feminist reformers developed a model marriage contract that would build the requirement of consent into a husband’s decision to take a second wife.

Even though she applauds the extensive work done by these initiatives, like the Musawah movement, she criticizes the fact that they “have aligned surprisingly well with the clichéd causes familiar to us through our study of sensational media and pulp nonfiction.”

The strength of Abu-Lughod’s message is the intricate and complex stories of Muslim women that she shares with readers. In these stories, it becomes extremely difficult to distinguish between oppression and the consequences of colonialism. On many occasions, the concept of choice, so much cherished in the West, is blurred by poverty, economic and social problems.

So finally, after reading Abu-Lughod’s book, can we answer the question, “Do Muslim women need saving?” The answer isn’t as obvious as some authors, politicians and journalists want us to believe.

Abu-Lughod’s book isn’t a justification for Muslim women’s oppression. It is a plea for the humanity of all women, regardless of their religion or race.

Monia Mazigh was born and raised in Tunisia and immigrated to Canada in 1991. Mazigh was catapulted onto the public stage in 2002 when her husband, Maher Arar, was deported to Syria where he was tortured and held without charge for over a year. She campaigned tirelessly for his release. Mazigh holds a PhD in finance from McGill University. In 2008, she published a memoir, Hope and Despair, about her pursuit of justice, and recently, a novel about Muslim women, Mirrors and Mirages. You can follow her on Twitter @MoniaMazigh or on her blog www.moniamazigh.com