Canada’s first-quarter GDP report was not just “atrocious,” as predicted by Stephen Poloz. It was downright negative: total real GDP shrank at an annualized rate of 0.6 per cent (fastest pace of decline since the 2008-09 recession). Nominal GDP fell faster (annualized rate of 3 per cent), as deflation took hold across the broader production economy (led, of course, by energy prices). This sets the stage for a politically explosive second-quarter report, which will be released by Statistics Canada on September 1. The official definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth. This definition, of course, is utterly arbitrary: it can feel like a recession in the economy (with rising unemployment, poverty, and pessimism) even if real GDP is sluggishly expanding. Nevertheless, if the second quarter number is also negative, then by that conventional definition, Canada will be in a recession — just in time for the federal election campaign.

What are the chances of that happening? Here I parse the odds.

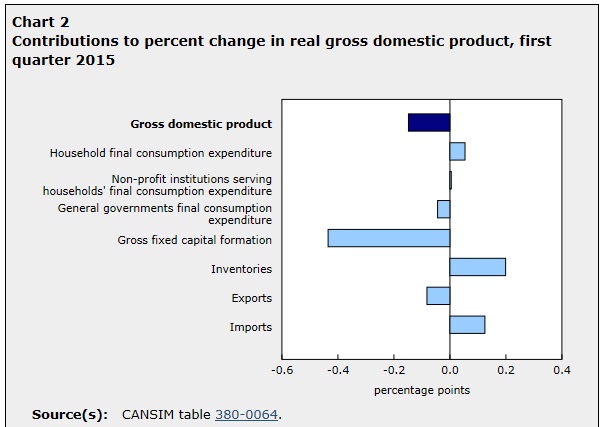

The best visual guide for eyeballing the odds of a second quarter of negative growth is the figure which was published in the first quarter results (reported in The Daily last Friday, May 29) decomposing the sources of GDP growth for the quarter. It weights the change in each component of spending by its importance in the overall picture:

It is immediately obvious from this figure that the decline in GDP was led by a painful decrease in business non-residential capital spending (down 4 per cent in the quarter, and knocking close to half a point off GDP in the quarter). I previously suggested that the downturn in business investment, concentrated in the petroleum industry, would be the most dramatic channel through which the lower oil price would affect GDP; actual oil production, on contrast, is going to keep increasing on the strength of previous investment.

However, business investment was not the only source of decline. Exports and government consumption spending (i.e. government spending on current services) also shrank. Austerity at all levels of government, therefore, is now making the economic situation worse — at a time when we clearly need more demand from the public sector, not less. There were modest contributions to GDP coming from household consumption (which grew at the slowest pace since the last recession) and from imports (which contracted slightly more than exports, with the result that the combined foreign sector actually made a slight net contribution to GDP in the quarter).

The biggest single source of growth in the quarter, however, was inventory accumulation: up by $11.5 billion in the quarter (following another big inventory build in the last quarter of 2014). Growing inventories can be a sign of slowing demand by consumers, and it can spark a decrease in future orders by wholesalers and retailers.

The big question now is how will these various components of growth evolve in the second quarter (which is now already into its last month). The decline in capital spending is certainly not turning around: if anything, it is getting worse, as petroleum companies respond to shrinking cash flow by further rolling back their new investments. (Canada was dangerously dependent on the petroleum sector for up to 30 per cent of total business capital investment; the present situation reminds us precisely why that is an enormous economic risk.) Government spending cuts are still in process; even as it balances its budget (with the help of a good dose of blatant fiscal manipulation: selling off assets and raiding the EI cookie jar), the federal government’s spending restraint is as harsh as ever. Meanwhile, provinces are also still in austerity mode. Exports are also continuing to decline: nominal exports fell 0.7 per cent in April (led this time by non-energy exports), and the decline was even worse in real terms. So all three of the bars that are negative in the figure above, are likely to remain negative in the second quarter as well.

What about the items on the positive side of the figure above? Consumers are a wild card. The weakness of consumer spending in the first quarter was perhaps the most surprising aspect of the GDP report, likely reflecting a broad-based lack of confidence. There is no obvious reason to think that has changed in the current quarter. Imports are falling in tandem with our exports, so the net foreign balance will likely have no impact on second-quarter GDP. Inventories are another wild card. There is good reason to believe that bar could shift to the negative side in the second quarter, driven both by order adjustments from retailers (responding to slower consumer sales) and by some big second-quarter restructuring in the retail sector (Target, Sony, Best Buy, and others). It is highly unlikely the inventory build will get stronger in the second quarter.

Leading indicators for output in the second quarter are also not encouraging. Employment fell by 20,000 jobs in April. Today’s jobs report for May will be a crucial new piece of evidence regarding the macro trajectory. Housing starts in April were down 8 per cent year over year. Exports are declining, as noted. Oil prices have bounced back somewhat since the first quarter; while that doesn’t directly affect real output, it could ease the deflationary pressures on nominal incomes and hence reinforce consumer spending. On the other hand, it also recreates some pain at the pumps for Canadian gasoline consumers.

The end balance could be determined by some unusual one-off items. Fiat-Chrysler’s big auto plant in Windsor partially came back on stream in the middle of this quarter, after a lengthy shutdown for re-tooling. That will add slightly to national GDP. On the other hand, wild fires in northern Alberta are forcing the shut-in of significant volumes of oil production. Harsh weather is said to have held back Canada’s GDP in February (keeping shoppers at home), and that won’t be a factor in the spring (on the other hand, that same cold weather also boosted the real output of Canadian utilities). I’d say all these one-off factors are likely a wash.

Even simple arithmetic can become a factor in making predictions like this. GDP fell in each month of the first quarter (significantly in January and March, only slightly in February). Closing GDP in March was therefore a full 0.5 per cent below its December value (measured by the monthly GDP by industry tally). That means even if GDP merely remained stagnant through the second quarter, the average value for the second quarter will be well below the average for the first quarter. To get a positive GDP average for the second quarter would require sustained growth through the quarter (to offset the decline that happened during the first quarter). This arithmetic heightens the chances for a negative second quarter number.

All this being said, I place 60-40 odds that the second quarter GDP number will be negative. Even if it’s weakly positive, of course (the best possible outcome at this point), it’s no consolation for the stagnation and pessimism that clearly dominate the national outlook. The Harper government’s traditional claim to be the “best economic managers” — never justified even at the best of times — has crumbled completely in the last year.

And like any economist, of course, I reserve the right to change my mind!

Postscript: May Employment Numbers

May’s labour force survey reported strong hiring in Canada that month: 59,000 new positions, all in paid private sector work (not public sector or self-employment), a mixture of full-time and part-time. That would definitely suggest continued growth in output during the month. This new information will thus reduce the odds of a second quarter of negative GDP growth accordingly. However, given the unpredictability of the monthly LFS numbers, and the demand-side and arithmetic issues indicated above, I would still suggest a significant chance average 2Q GDP will fall below the 1Q number, thus constituting an official “recession.”

Jim Stanford is an economist with Unifor.

Photo: pmwebphotos/flickr