Like this column? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

While the 2015 federal election featured many firsts, one new electioneering element stood out baldly in the social media age.

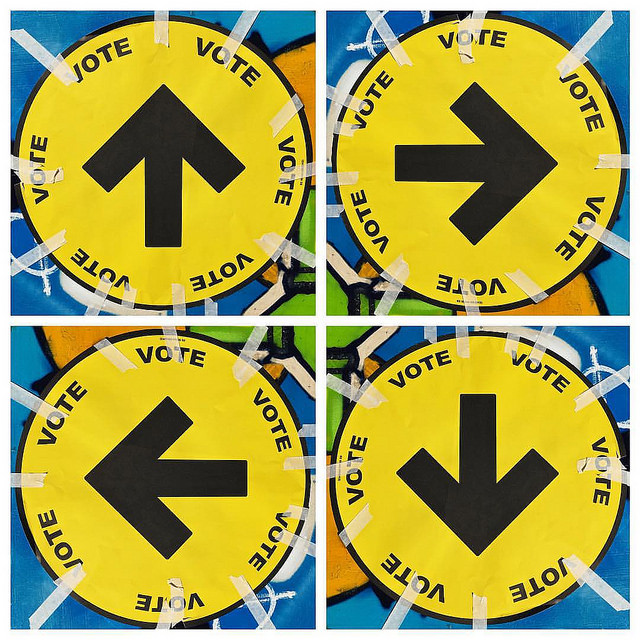

It was a politically conservative campaign wrapped in progressive colours that insidiously showed itself on countless Facebook pages, Twitter feeds, and in a campaign promoted by media personality Rick Mercer. The unashamed fetishization of voting — turning the placement of an X on paper into a moment of important self-regard (complete with ballot box selfies) — was designed to make people feel like they’d helped cure cancer. And while it felt good to see Harper trounced from the Prime Minister’s Office, the results won’t exactly fix what ails Canada.

This hyper celebration of voting as a panacea seemed to reflect an age in which cheap and easy commitments — changing our Facebook pages to read “Je Suis Charlie” (following the Charlie Hebdo shootings) or holding up selfies reading “Bring Back Our Girls” (kidnapped by Boko Haram) — do more to make us feel good about ourselves than seriously address the challenges we face.

Voting is the absolute minimum task one can perform in a democratic state, but by elevating it to the level of heroism, we paper over serious questions about what, exactly, is achieved after 10 long weeks, tens of millions of dollars spent, and untold volunteer hours going to three mainline parties who are not terribly different in their fundamental outlook. And as for those who don’t vote? They’re treated like the party poopers who won’t put on a breast cancer awareness pink ribbon, and told they cannot complain if they don’t like the results.

As with any major media event, whether it is a federal election or a baseball playoff, the idea that one must join and share the same collective experience has become a sacrosanct matter of course, even if you don’t know a stolen base from a question of parliamentary privilege. If you can’t say you saw the famous seventh inning that turned the Jays into divisional champions or that you waited two hours in the rain and snow to cast your ballot and “have your say” on Monday, you’re not likely to be a popular contributor to the water-cooler chatter.

But while voting is one element of a democratic system, if it is to mean anything, even more crucial is having something worth voting for. How many people went to the polls on Monday and held their noses, thinking as they made their pick that, in a desperate ABC (Anybody But Conservative) moment, they were forced to choose the lesser of evils? What does it mean to “have your say” when most voters would be embarrassed pink to spout the somnambulant soundbytes of the parties’ leaders (“ready for change,” “real change,” and “protecting the economy”)?

One is reminded of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s gradual radicalization, when he came to the conclusion that integrating lunch counters meant nothing as long as those enjoying this new freedom could not afford to buy lunch. How can Canadians enjoy a truly democratic choice when, according to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the richest 86 people in this country have the same wealth as the poorest 11.4 million Canadians, and not a single major party is willing to seriously challenge and dismantle the sources of such gross inequality? On a broader level, how can anyone place their future hopes in a party that refuses to recognize the seriousness of climate change and Canada’s single biggest contributor to planetary peril, the Alberta tar sands? And what does it mean as a settler to vote without pausing to remember, and perhaps act upon, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission conclusion that Canada is a nation built on what it deemed a “cultural genocide” waged against Indigenous peoples?

When voting is treated as the most important thing you can do in a democracy, it becomes a statement of political and intellectual constipation that encourages us to accommodate ourselves to a status quo of incredibly narrow choices, with only minor tinkering proposed by mainline parties who swear allegiance to such a system. Privileging voting above all else also delegitimizes the very grassroots formulations that both created and sustain those best elements of democratic countries, from the community organizing that leads to the creation of women’s shelters, co-op housing and credit unions, to organization of demonstrations, strikes, and direct action. As the old bumper sticker read, “If voting made a difference, it would be illegal.”

Voting does not equal or encourage participation in decisions affecting our daily lives, either, which is why it is so easy for mainstream institutions to promote it as the noblest of political actions. Indeed, it was the very outbreak of participatory politics in the 1960s and ’70s that led the planet’s leading power brokers (including members of Pierre Trudeau’s cabinet) to form the Trilateral Commission, whose report, The Crisis of Democracy, shivered with the conclusion that the social movements forcing real changes in those tumultuous times resulted from an “excess of democracy” that had to be reigned in through economic and political austerity (a lowering of expectations) and the elites’ viewpoint that “the effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and non-involvement on the part of some individuals and groups.”

Could voting make a real difference? When the NDP uprooted the “socialist” bogey-word out of the party’s constitution in 2013 in an effort to make itself more “electable” (supplanting the old with a new focus on balanced budgets), it was one final blow severing its roots in the 1933 Regina Manifesto when, as the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, the party proudly declared: “We aim to replace the present capitalist system, with its inherent injustice and inhumanity, by a social order from which the domination and exploitation of one class by another will be eliminated.”

But what if the NDP, for example, returned to its roots as a party that refused to make such accommodations to a cruel economy, as when it fought for universal health care? Look south of the border to the popularity of socialist Bernie Sanders (and a Pew research poll that finds 49 per cent of Americans under age 30 have a positive view of socialism) and overseas to the rise of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of Britain’s Labour Party. Take note as well of the anti-austerity victories posted by Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece, and one can see that condemning the current system as unfair is hardly an unpopular notion, especially when such positions reflect broad popular forces that have created a critical climate for systemic change. That such parties have a long way to go is without question, but they have also given strength to the notion that substantive change can be wrought through an electoral politics that goes beyond passionless calls for balanced budgets, tax credits and reduced ATM fees.

But does change have to wait another four years for a new party to come along, or can we get to the business of organizing ourselves into a social force that cannot be ignored? One answer, as African-American poet June Jordan reminded us, is this: “We are the ones we have been waiting for.”

Matthew Behrens is a freelance writer and social justice advocate who co-ordinates the Homes not Bombs non-violent direct action network. He has worked closely with the targets of Canadian and U.S. ‘national security’ profiling for many years. An edited version of this column first appeared in NOW Magazine.

Photo: Francis Mariani/flickr

Like this column? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.