Who knows what to make of war, even when it’s happening as we speak and read?

It so easily gets distanced: it’s foreign, literally and psychologically — like the sieges of Mosul or Aleppo. Young men die there in battle each day. But for us, it’s a mention in the news, so like yesterday’s and tomorrow’s that we normally slide past.

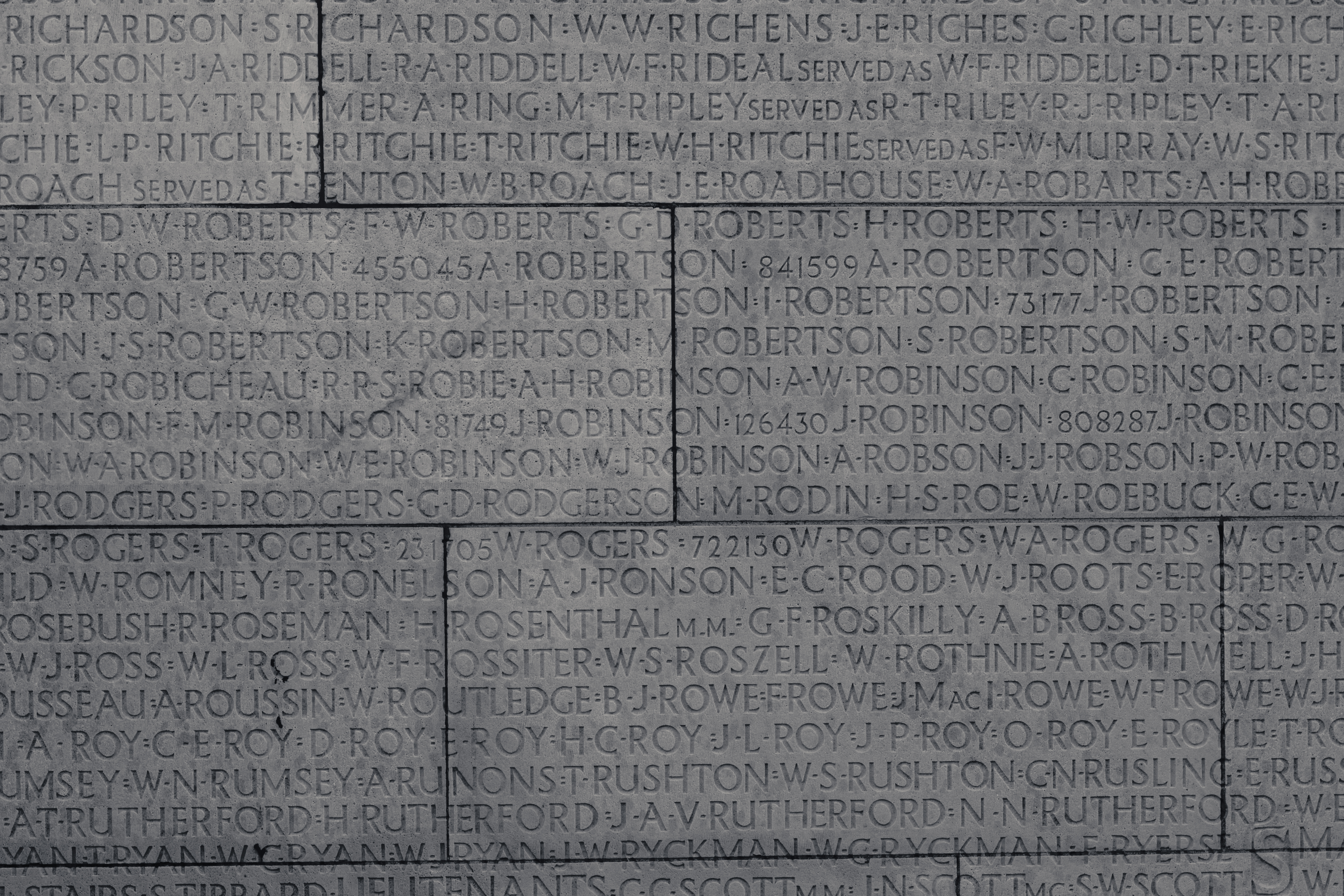

Military deaths are rarely reported; civilian deaths, sometimes. Names — they have none. Their deaths pass as quickly as people in cars driving in the other direction on the highway — whoosh — lives as complex, hopeful or fearful as ours, yet we never register them as individuals.

Can people actually be dying every day to win back these cities for their side? Yes. They wake each morning knowing some won’t go to sleep that night. Imagine the agony if it was us and our kids.

Then what can we make of the centenary of Vimy Ridge, a battle a century ago, April 9 to 12, 1917? Yet it can be that distance itself that finally lends sense.

Here’s a peculiar example. Shortly after the war, in 1925, English crime diva Agatha Christie wrote a short story, “Witness for the Prosecution,” a classic revisited often — as a play, a film, for television — for almost as long as Vimy has been commemorated. It never mentions the war, but like the war, it was about murder and guilt. In the original, the murderers get away with it, ingeniously. This bothered Christie who almost always made the guilty pay; so in her stage version, in 1953, they are killed, deservedly. But still, no mention of war.

Then, in the most recent BBC-TV version, last fall, with Christie long dead, there’s a brilliant twist. The murderers survive and thrive, but the lawyer who got them off, kills himself when he realizes their guilt. Why? Because by winning the case, he was trying to expiate his own guilt: he’d survived the war but his son hadn’t. So the guilty don’t go free — which would have pleased Christie — but we find out more about where guilt truly resides, and it’s not simple.

In this latest remake of a tale of death and guilt, the war finally speaks its name, but in a way Christie couldn’t: she was too English, too of her time. It rings truer, and just as cleverly, as her versions. It’s as though it’s taken this long for the full significance of that war to work its way to the surface, like shrapnel. The story and its meaning existed on some autonomous level, just waiting, separate from its author, who merely unearthed it and left it for others to improve at a later time. Trust the song, not the singer.

I think also of English poet Edward Thomas, who died on the first day of the Vimy attack, April 9. A stray shell landed near his battery and a “pneumatic concussion” sucked the air from his lungs so his heart stopped. That’s all, no wounds.

He’d just started writing poetry with encouragement from his friend, U.S. poet Robert Frost, and he wrote a lot, sometimes a poem a day, fine work but rarely about war. Unlike other war poets, he didn’t take the war as his subject, but the war made him feel the urgency of saying what he had to say.

Thomas could have stayed home without censure, due to his age, but he joined. His motives were murky (the fog of war, extended). He felt Frost might have been criticizing him for dithering in his poem, “The Road Not Taken,” though, in fact, Frost wanted him to come to the U.S. and write there.

He enlisted finally out of a feeling of debt to England itself in a literal, landscape sense. He was a lover of English countryside and wrote about walks through it: Nothing really against the other side but a deep feeling he should protect his own place.

In Vimy’s time war was often seen as the noble force that “turns a people into a nation” (German nationalist Heinrich von Treitschke, quoted by Pankaj Mishra), which is the claim made often about Vimy: it created Canada.

But today it’s the more homely justification given by Thomas that sounds familiar. Young Canadians or Americans are sent off to die in Iraq or Afghanistan, under the dubious claim that they too are making “the homeland” safe.

This column was first published in the Toronto Star.

Image: Flickr/Andrew//

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism.