Netflix says it’ll voluntarily pour $100 million a year into Canadian film production over the next five years. The response here has been typical Canadian ingratitude: Is that all? Or: They’re only doing it to evade being taxed directly. I wonder if that irritates Netflix, or just perplexes them. What’s with these people?

My own reaction is that I’m worried less about Netflix than about Newsflix. Whatever its troubles, Canadian dramatic art is in far better financial shape than Canadian journalism. Does that sound like the most artless segue ever?

Allow me to double down. I think there’s been a peculiar but strong historical symbiosis between Canadian journalism and Canadian film culture. This was always the land of documentary, shading into drama. The first feature doc ever made (more or less, these are inherently specious claims) was Nanook of the North, done by an American but made here, with early intimations of docudrama. The very term documentary was coined by a Scot, John Grierson, who migrated here and created Canada’s luminous National Film Board.

The first Anglo-Canadian dramatic feature, 1964’s Nobody Waved Good-bye, was made by Don Owen, at the NFB. Our films have retained a doc-like feel, as if the national sense was shaky enough that it needed a sense of being anchored in the real world, something that actually happened, because you probably read about it, eh?

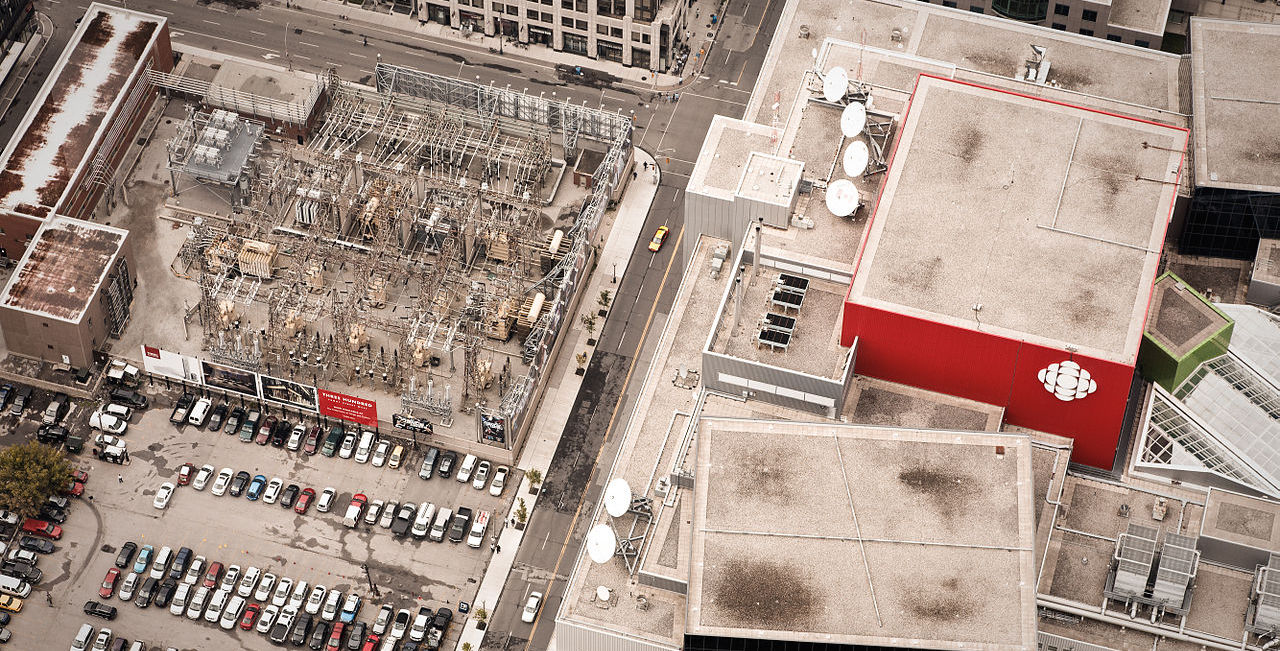

Add the national bent for news-based satire, from Max Ferguson’s brilliant daily radio sketches through Rick Mercer or all the Canadians who built satire in the U.S. One of Canada’s sublimest dramatic creations, Ken Finkelman’s The Newsroom, was based on CBC news, and filmed in the bowels of the CBC. It couldn’t have existed without Canadian journalism, but transcended it utterly.

CBC, in fact, should be a key to resolving journalism’s current crisis. That crisis is based on the sudden disintegration — like a milkweed pod, poof — of the advertising economic model. It was always accidental; there’s no natural affinity between ads and news, but it worked, till internet behemoths like Google and Facebook swiped all the ad revenue. Now news outlets are gasping for air; many have already expired.

The obvious solution is public funding, as with other national necessities, like health care or the Armed Forces. For some reason, many people, journalists included, find this odious and a threat to press freedom. Why corporate pressures, via ads, are seen as less menacing than government ones, I have no clue. But CBC already exists and gets about $1 billion in public funds each year. So there’s your new model, and it’s been accepted for decades.

Sadly, CBC in its current incarnation is a wretched exemplar for news. For its own tawdry reasons, it’s chosen to focus mainly on crime, weather and consumer tips. Its lead story for the Houston hurricane was how much it would cost Canadians at the pumps. That’s an insult to the intelligence and citizenry of those whose taxes sustain it. CBC’s motive for this contemptuous dumbing down was ostensibly to multiply eyeballs. The result is that more people now watch not just CTV news with Lisa Laflamme, but Global news with Dawna Friesen. Global for God sakes!

So I’m not arguing for support to the institutions just as they are, including the CBC. Fortunately, other models exist, like Vice News Canada. Vice News is a complex international octopus but has a lively Canadian component. Its U.S. reporter, Elle Reeve, did the splendid embedded coverage of racism in Charlottesville as well as a piece on progressive liberal wrestling heel Dan Richards. It is a kind of newsflix.

Here’s my proposal, meant to gradually transition to a solvent news media with public financial backing: take CBC’s entire news subsidy and funnel it to news outlets, old and new (Vice News Canada, Jesse Brown’s Canadaland) that, unlike CBC, serve a public purpose. Turn CBC basically into a spigot. Add more funds as required. If CBC news ever smartens up, they can apply to get some of it back.

I know it sounds a bit improvised but we live in an era of mishmash. Work and leisure, culture and the economy, news and art, are less distinguishable than they were. Most jobs now involve an (albeit routinely overstated) element of creativity. It’s all courtesy of the internet, which, at its electronic root, is about connections.

There you go. Crisis solved. Next?

This column was first published in the Toronto Star.

Image: Benson Kua/Flickr