On Friday July 11, the Supreme Court of Canada released a unanimous decision on Grassy Narrows First Nation v Ontario (Natural Resources). The decision, concerning First Nations treaty rights, was written by Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin. The Court held that only the Province of Ontario has the right to “take up” lands in the Keewatin area under Treaty 3 in Northwestern Ontario.

Taking up lands

This case began as an application for judicial review challenging a forestry licence Ontario issued to a pulp and paper manufacturer, which authorized clear-cut forestry operations within the Keewatin area. The contested issue was whether the licence infringed Wabauskang and Grassy Narrows’ harvesting rights under Treaty 3, and whether Ontario could issue licences under the “take up clause” in the Treaty, which allowed lands to be used for settlement, mining or lumbering by the government. This application was quashed in 2003 because the issue could only be resolved at a full trial.

After hearing 75 days worth of evidence, Justice Sanderson made an overwhelming finding in favour of Grassy Narrows. Justice Sanderson held that based on the intentions of those that negotiated the Treaty, the power to take up lands in Keewatin under the take-up clause in Treaty 3 was vested with the federal government and not Ontario. Consequently, Ontario was held to have no authority to infringe their treaty rights. At the Ontario Court of Appeal, Ontario was successful.

At the Supreme Court of Canada, Grassy Narrows argued that the Treaty negotiations “did not focus on the meaning of the Taking up Clause.” They also argued that the negotiation of Treaty 3 was between the First Nation and the Federal government, not Ontario.

The duty to consult and accommodate

The Supreme Court held that the taking up of land by Ontario is limited by the potential action for treaty infringement. The test for infringement in this case is if the Ojibway are left with “no meaningful right to hunt, fish or trap in relation to their territories.” The Court held that the Crown’s right to take up lands under Treaty 3 is subject to its duty to consult and accommodate First Nations interests beforehand.

Bruce McIvor, a lawyer who argued on behalf of Wabauskang First Nation, another Treaty 3 First Nation, said on First People’s Law website that, “While technically a ‘loss’ for Grassy Narrows and Wabauskang, the decision will most likely prove a powerful tool for ensuring that Ontario, and other provinces, respect treaty rights.”

According to McIvor, “The Court was unequivocal that while Ontario can exercise its interest in Crown lands, its authority is subject to Treaty and is burdened by the Crown’s constitutional obligations, including fiduciary obligations.”

McIvor was alluding the Court’s inclusion of the Crown’s fiduciary obligations, which must be exercised with the Honour of the Crown when dealing with Aboriginal interests. Aboriginal interests, including Treaty interests, place a burden on the Crown exercising its power.

The Tsilhqot’in decision similarly provided guidance on the issue of the Crown’s fiduciary duty to Aboriginal peoples. The Court in that decision held that the Crown has a fiduciary duty owed to Aboriginal people when dealing with Aboriginal lands.

The Court also held that on the issue of justification that reconciling the Aboriginal interests means the Crown can justify the broader public interests of a s. 35 infringement of Aboriginal lands.

This may be a situation where the Court is reconciling the interests of the broader community to justify the infringement of Aboriginal interests.

What’s next?

“While we hoped the Supreme Court of Canada would respect our treaty, we are determined to see Treaty 3 respected,” said Chief Roger Fobister of Grassy Narrows First Nations in a press release.

Similarly, Ontario Regional Chief Stan Beardy stated in a press release that this decision is “a breach of Canada’s obligations to uphold international laws/standards and undermines Indigenous laws that have already been in place for centuries.”

The Regional Chief of Saskatchewan, Perry Bellegarde who holds the Treaty portfolio for the Assembly of First Nations also went on record as saying that, “I remain unconvinced that justice will be achieved through Canadian domestic courts when it comes to the interpretation of our international Treaties.”

Bellegarde went on to say that, “[T]his also needs to be addressed according to international standards as affirmed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

These statements leave open the possibility that the First Nations of Grassy Narrows may be bringing their Treaty concerns to international forums in order to uphold Canada’s international obligations.

Christina Gray is a student-at-law at Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto. She holds a Juris Doctor and Art History degree from the University of British Columbia. She is a proud member of Lax Kw’alaams Tsimshian Band, but is also of Dene, and Metis descent.

On July 29 at 8:30 p.m. at Ryerson University, there will be a Public Forum with Stephen Lewis, Roger Fobister, Judy Da Silva and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. They will discuss issues arising out of this decision and concerns from the community.

Proceeds from the Public Forum will go towards sending Grassy Narrows community members to the River Run 2014: Walk with Grassy Narrows for clean water and Indigenous rights on July 31 at 12pm at Grange Park in Toronto.

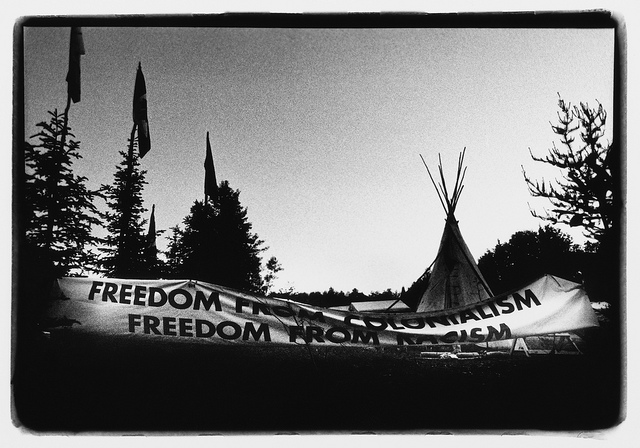

Photo: flickr/Howl Arts Collective