A magnificent talent was almost destroyed by social prejudice masked as “care.” Artist Judith Scott, whose art now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, was locked away in an institution for 35 years.

Her twin sister, Joyce Scott, tells the true story of her journey to help free her sister in her new book, Entwined. Judith was born in 1943 with an intellectual disability. Her story is a profound lesson in moral courage. It shows the power of one compassionate individual to act. It demonstrates how each of us can work to shift society in a positive, caring direction.

Scott’s story is very timely. Carla Qualtrough, The Federal Minister of Sport and Persons with Disabilities, is inviting Canadians to speak up on a new accessibility law. This is long overdue. Canada has lagged behind the U.S. for 26 years. Since 1990 the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) has been asserting the human and civil rights of the intellectually disabled to live in the community. “Right now, within our current legal framework, the rights of those of us with disabilities don’t kick in… until our rights have been violated,” Qualtrough said while announcing the legislation. “The current system unfairly burdens Canadians to ever defend our rights.”

Indeed. How does someone with an intellectual disability fight back when their rights are violated? They are virtually defenceless. Which brings me back to Judith Scott’s inspiring story.

In 1950, at the age of seven, Judith Scott’s future was written off. She was locked away in state institutions for the “mentally retarded.” In Entwined, Joyce Scott remembers her first visit to Judith’s institution,

I find myself in a dark hallway with doors that all look the same… I open one door after another. I keep opening them, looking in, trying to find the right one. Instead I find rooms full of children, children with no shoes, sometimes with no clothes. Some of them are on chairs and benches, but mostly they are lying on mats on the floor, some with their eyes rolling, their bodies twisted and twitching. They are moaning and reaching into the air when there is no one to reach back. Only the hot heavy air. And there are terrible smells, sweaty smells, bathroom smells where there is no bathroom.

Thirty-five years later, at a Buddhist retreat, Joyce had an epiphany. She realized that she had the power to save Judith and be reunited with her fraternal twin. Joyce describes her motivation:

I had this incredible awareness of how completely nuts it was that Judith would be in an institution when we could be together. I came to realize that when my parents made that decision [to institutionalize Judy] we were both just little girls and I was completely powerless, of course, to impact that. Somewhere inside I still had that sense of powerlessness and it was the meditation that changed everything.

From that day in 1985, Joyce worked to get her sister freed, and to move from Ohio to be with her in California. Joyce was way ahead of her time. Her decision to rescue her sister was five years before the ADA — and 14 years before the landmark Supreme Court Ruling, Olmstead vs LC. To this point, the U.S. has been doing a better job in protecting the rights of the disabled than Canada. In 2009, the Civil Rights Division launched an aggressive effort to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision in Olmstead v. L.C., “a ruling that requires states to eliminate unnecessary segregation of persons with disabilities and to ensure that persons with disabilities receive services in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs.”

People with Down syndrome are too often considered a burden and dumped into institutional warehouses. While many of us would like to believe that the dark time of putting people with intellectual disabilities away is finished — it is not. People with Down syndrome are still segregated.

The Ontario Ombudsman’s Nowhere to Turn report from August 2016 confirmed that Ontario faces a systemic crisis: people with Down syndrome are being “placed” in unsuitable housing including long-term care homes, hospitals and even jails. Global News reported on July 22, 2016 that over 2,900 adults with developmental disabilities are in Ontario long-term care homes now.

The laws are not working to protect people with disabilities. While the Charter of Rights and Freedoms states that we are all to be treated equally, without discrimination due to mental or physical disability — these violations are happening all across Canada. There is a conveyor belt of people with intellectual disabilities going into long term care homes and other institutions. The National Task Force on Living in the Community has found that “In many provinces and territories persons with intellectual disabilities are being admitted on a routine basis to institutions, directly violating a stated policy of deinstitutionalisation.”

Judith and Joyce Scott’s story is life affirming. It shows how moral courage can cut through the social stigma that secretly discounts the lives of those with Down syndrome. Entwined tells how Joyce worked to get her disabled sister freed from an institution — and then created a nurturing environment where her sister’s talents could flourish and grow.

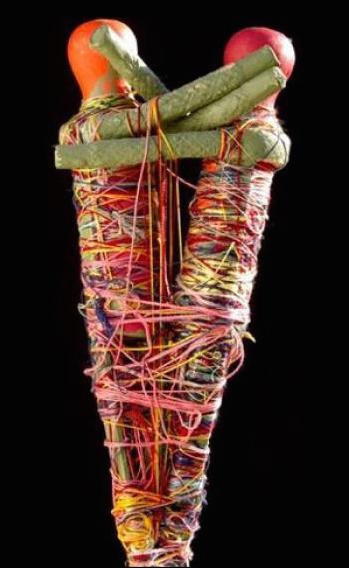

Judith Scott’s sculpture “Twins.” Photo by Dr. John Cooke/Wikimedia.

The fact that Judith Scott developed into an internationally recognized artist whose fibre art is collected by major museums should be celebrated around the world. Joyce Scott’s activism and moral courage should be celebrated around the world. We need more people like her to shift society to be more compassionate and caring.

As Canadians we have a chance right now to make revolutionary changes. Minister Qualtrough is inviting Canadians to participate in consultation to create accessibility legislation. While fixing elevators and ramps is important, the most glaring problem is how to protect human rights for the intellectually disabled.

How many more Judith Scotts are there?

December 3 was the International Day of Persons with Disabilities.

Franke James is a Vancouver-based activist, artist and author focused on freedom of expression, disability rights and the environment. She is the winner of the 2015 PEN Canada/Ken Filkow Prize and the 2014 BCCLA’s Liberty Award for Excellence in the Arts. Franke is a caregiver and advocate to her ”Pretty Amazing“ sister, Teresa Pocock, who has Down syndrome. Their three-year campaign recently helped Teresa win an apology from the Ontario government in November 2016.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism.