To make my mother come back from her 3 a.m. drive, that weekend I hustled in the semifinals against the Alaskan team so I could become MVP. In our league, I was known for playing brutal defence, and blood-thirsty parents liked to watch my “mean streak,” which flowed through me like an all-you-can-eat meal.

I believed that if I won a medal, there was a slim chance my parents might like me, that my mother might come back, even if the kids at school despised me, because it seemed fundamental that one of your parents should feel obligated to you via genetics or societal pressure. Wasn’t the main reason you reproduced to create the same, if not a better, version of yourself? I sensed that I was an irritation – like dust lodged in the eye, or a small piece of meat stuck between the teeth. And friendless, still. I was horribly lonely. However unmotherly my mother was, I needed her home.

On my shift, I charged down the ice, delicately stick-handling our prized puck, but tripped over someone’s stick and somersaulted into the wooden boards like an amateur acrobat. A girl punted me with her skate. I was trapped on my back, and another four or five piled up and pummelled the shit out of one another – our fathers’ live weekday entertainment. This was guerrilla hockey for girls who were practically apes, and I thought I was the baddest King Kong in the arena (a result of watching too many Sailor Moon cartoons). Boxy gloves were flung down. Black helmets were snapped off and tumbled onto the shimmery ice, little guillotined heads bouncing happily along.

To survive this beastly brawl, I was sly enough to shut my eyes and play dead. But a sick feeling lurched in my tummy, like I had swallowed a writhing beetle or part of my own tongue. It was a feeling that I didn’t understand – absolute wrongness.

Suddenly queasy, I threw up a little in my mouth but couldn’t tell if I had smacked my head too hard on the boards. I blacked out for a second, abruptly falling asleep. When I woke up, the paramedics said I had a minor concussion. But I could still perform to win back my mother, so I jumped up and insisted I play now. My skull thumped, helmet suddenly squeezing too tight, something perhaps not right. I felt my front teeth with my tongue, the bottoms were lightly chipped, my mouth guard stupidly left at home. No blood – not like last time I was clobbered in an offside fight. And not like when my father splintered his molar chomping into a walnut, gargling up gritty crumbs of ground-up enamel and nut.

I was going to be okay, and I was going to be victorious. I did not care if my team won, only if I won MVP overall. This was my deeply troubling mindset at the time: to appease my father and fix my mother.

A period later, I charged a girl centre ice and attacked ferociously, cracking the fleshy back of her lower leg with my stick. The shin guard obviously did not extend fully around. There was just the fuzzy, soft hockey sock to defend her spongy skin, and we both knew something had gone very wrong. She dropped. The linesman and referee allowed us to skate around for a few fast seconds. But then there was a sick little animalistic scream in the arena that got louder and louder. The girl I had whacked was flat on her back. Thrashing her arms in a useless backstroke, she looked like she was having a psychotic break, gone ridiculously mad.

This did not feel real to me at all, as I was back on the bench seeing it all through the plastic screens of the ice rink. I felt that I was watching the action like it was a video game manoeuvred by a disembodied controller.

“How come the girl cry when she get hurt?” my father later asked me in the truck when the girl had been cleared off the ice by the paramedics and the game was finally over. In my fugue-like state, I did not even remember how we had won. “You know if she retarded? Possessed?” he asked. If there were a ghost in the hockey rink, we would know that my mother had inadvertently caught it too, much like how someone could accidentally encounter a ravenous bear in our backyard — shitty luck.

“I broke her leg,” I said, unsure whether I should feel guilty. His was a real question, like someone asking for the time or directions — my father didn’t seem to understand what crying was for and thought that I could clarify it for him.

In the backseat, I did not feel well, and I did not feel as if I deserved my thrilling victory. The coiling B.C. freeway loomed like a concrete serpent, and I could feel my insides twist dangerously, as if I were becoming unravelled, while my father drove us home. The foamy blackness outside felt like it had transferred inside me, gurgling like unruly diarrhea, and I wasn’t sure what was consciously right; I was afraid I didn’t know the answer. While my head tingled from lack of sleep and excitement, I thought about the screaming girl; how much was her own noise, and how much was the wicked ghost inside her?

It would take a while for me to understand that this incident was just another casualty of my father’s war for control, just an effortless battle outside the house that he could win: he needed to blame someone for his wife’s sudden disappearance, and I was desperate and gullible. He could have blamed my sister, who would have cried for at least half an hour, but I was a better scapegoat because I would be tormented for longer. Prone to guilty sulks, like my daily nosebleeds and constipation, I would have done anything to make things better, even though I had pretended not to care that my mother hadn’t said goodbye to me.

“The coach says it was just an accident,” I eventually blurted, ignoring the slimy blackness in my gut, which was expanding, like a serving of cold, hard rice, which I then mistook for indigestion. “But I have to write her a nice sorry card.”

“Don’t bother,” my father said, miffed because he hated inconvenience. “It’s just a game. And postage all the way to Alaska — yikes. I’m happy we won. Are you happy? If I’m happy, you should be very, very happy. Are you loser or winner, Lindsay? No loser in this family, okay? We have to beat up loser. Now because we won MVP, Mommy will come back.”

“Okay,” I said, because I really believed him, or because I really wanted to. That there was magic in the bronzy medals that my father hoarded like Viking treasure. These prizes from the tournament somehow made me worthy of his parental respect. Nothing in our family came at a low cost — we paid for everything. If I took home a prize that night, there was hope that my father would not blame me for my mother’s absence. I had done my delusional duty, like a good daughter, and my actions, the last ingredient in our homemade spell, would bring back my ghost-driven mother.

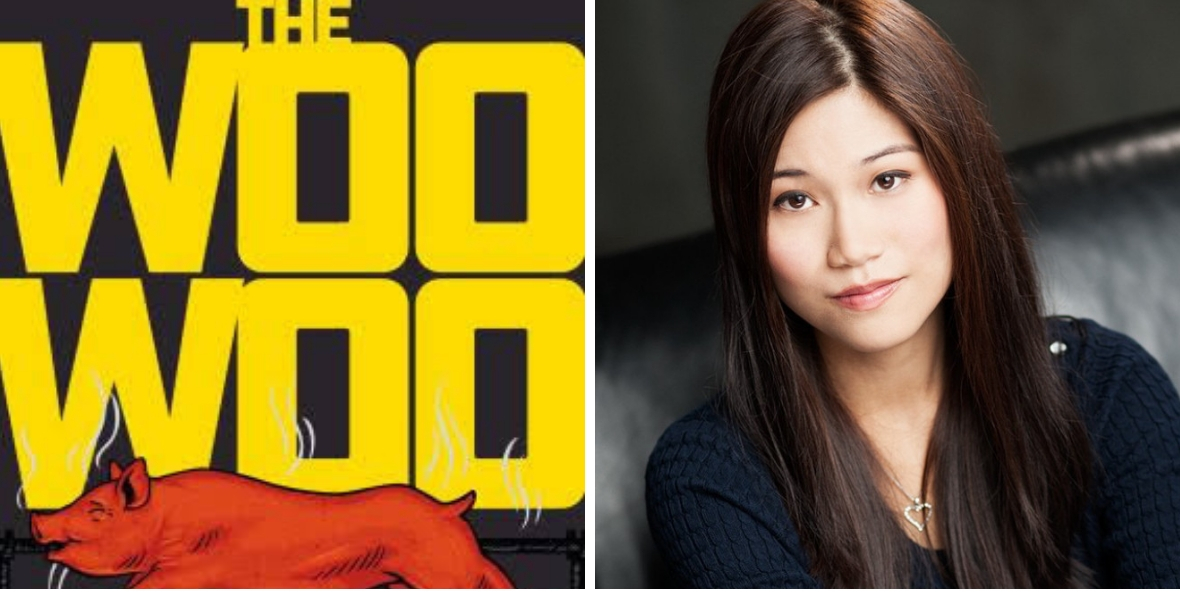

Excerpt from Chapter 3, “On the Ice,” of The Woo-Woo: How I Survived Ice Hockey, Drug Raids, Demons, and My Crazy Chinese Family, by Lindsay Wong. Published by Arsenal Pulp Press October 2018.

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!