What does the city forget?

Artists Maggie Hutcheson and Elinor Whidden make up the Department of Public Memory and it’s their job to find out. They gather living memories of Toronto’s public services and community organizations that have been cut or lost. Based on these memories they create art including commemorative signs for public sites like libraries, daycares, community programs and shelters.

Toronto Star columnist Joe Fiorito once described their work with a formula:

{A+ P} x W = C

In plain language: Art plus Politics times Wit equals Cheek.

In a recent exhibit for Myseum they created a number of installations called At Work In The Memory Archive where participants were invited to peruse unique archive files in small groups. The experience was part sit-down scavenger hunt, part civic discussion and part celebration of activism. The installations included Voices of Positive Women, Cleaners’ Action and Tent City.

In March I was invited to bring together some of the core Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC) members who worked to support Tent City. Tent City was a large homeless encampment on Toronto’s waterfront from 1998-2002. At its peak there were approximately 150 people living there in over 50 shacks and pre-fab houses. Many of the Tent City squatters were activists and their fight for housing resulted in their own win of a rent supplement program after their brutal eviction. This story was documented in Michael Connelly’s film Shelter from the Storm and in Cathy Crowe’s book Dying for a Home.

TDRC members were joined by former Toronto Star journalist Cathy Dunphy and Ryerson student Nicole Brumley, who captured the event with these images.

Jon Alexander is a longtime activist and TDRC member and recounts his experience at work in the memory archive.

Institutional inhumanity and art?

The clean, sterile whitewashed walls and the creaky wooden floor signal that you’re entering another world, one of reverence and remembering.

In a renovated but still charming creaky school classroom at Artist Youngplace, we came together to view the Tent City Archive. The austere former classroom surroundings seemed appropriate for an institutional setting like an archive.

It’s important in the affordable housing and other political movements to be able to look back to see where we’ve been — to learn from and be inspired by past actions and events.

People assembled, talking in hushed tones, a low buzz as they tried on their participants’ gear: neon-bright safety vests, reflective straps, sunny yellow hardhats, and dark coveralls.

I thought about the stereotypical art review — trying to plumb the creator’s intent and meaning, asking, was it “one’s inhumanity to another”?

The sterile setting led me to ask myself: What is the humanity of a temporary settlement, necessitated by a critical lack of affordable housing, by a national disaster?

Tent City organically sprouted from a scouting trip by folks looking to get away from an overburdened and horribly under-resourced emergency shelter system. The community persisted and survived from 1998 to 2002, struggling for hope and against many obstacles, natural and institutional. In the end, there was some measure of hope — many residents found housing through the rent supplements. Many remain housed today, though some have departed our world.

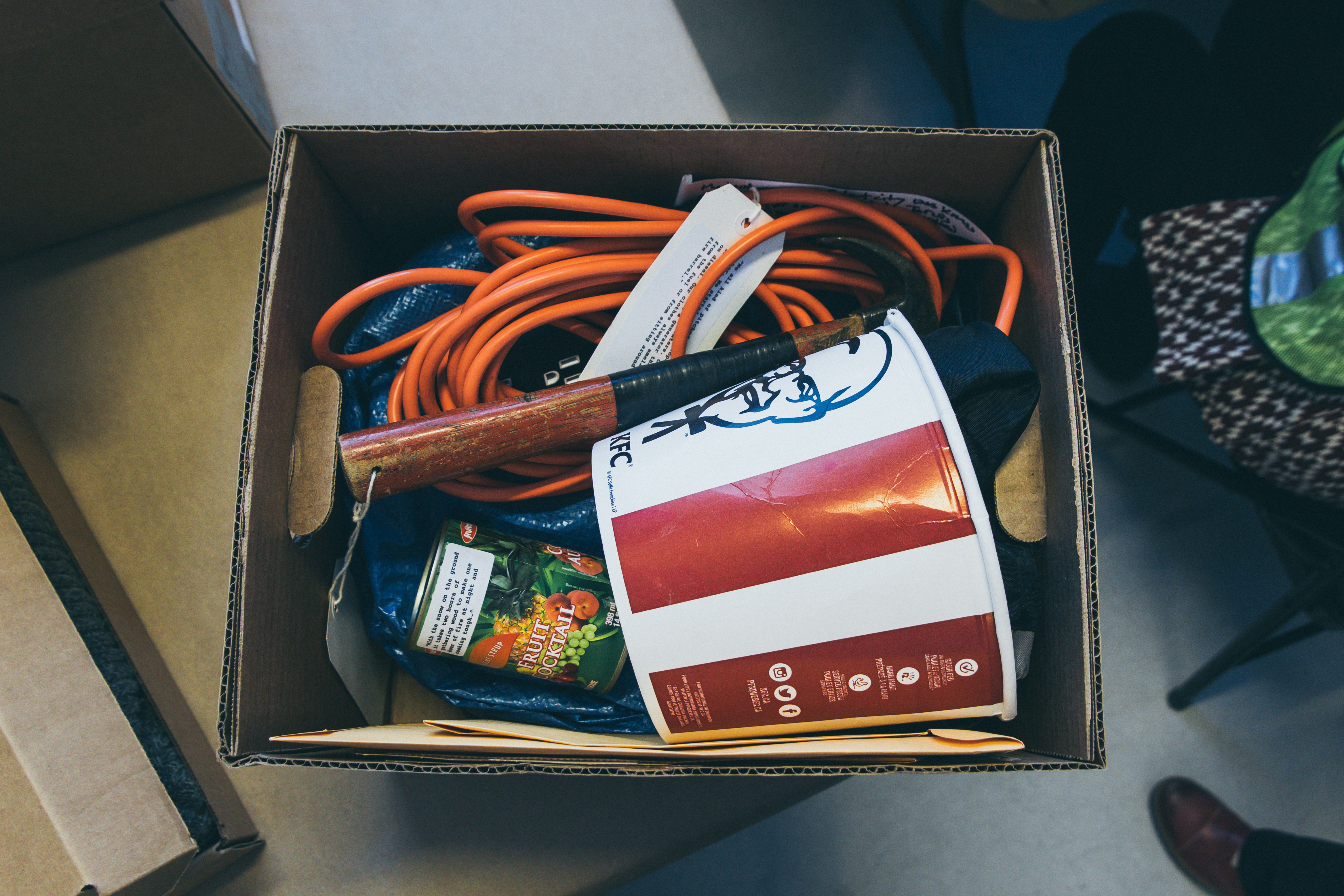

The format and presentation of the exhibit was fascinating. There was visual stimulation offered by the physical objects — a sign mock-up, maps, photos, reports, newspaper clippings.

There was a smoke-scented sweater from the nightly fires at the settlement, a crumpled KFC bucket representing communal meals and assemblies, a taped-up hammer, a pair of worn running shoes.

There was the audio stimulation on tape — the sometimes quiet, and the sounds of the Lakeshore (crickets, shore birds, vehicles rushing by).

We dressed up in the hard hats and reflective vests, and became members of the archivists’ working unit, to unveil and examine the archives from both a professional and artistic perspective.

It brought us to the intersection of city and lake, of housing and homelessness, of justice and struggle.

Photo credits: Nicole Brumley

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.