In 2017, journalist Martin Lukacs wrote a column for The Guardian comparing U.K. Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. “Jeremy Corbyn has shown us the meaning of a politics of genuine hope,” Lukacs wrote then. “What Trudeau has deployed has only ever been a politics of hype.”

Lukacs knew he’d hit a nerve from the way Liberal party insiders responded to his piece. “The crème de la crème of Liberal intelligentsia in this country had a meltdown on Twitter,” he recalls with a laugh. “So I thought — huh, I clearly hit a soft spot.”

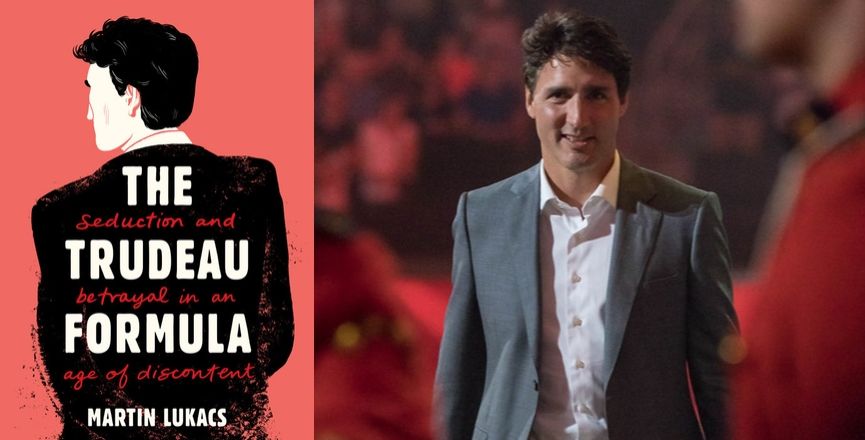

Lukacs’ investigation of that soft spot grew into his 2019 book The Trudeau Formula: Seduction and Betrayal in an Era of Discontent (Black Rose Books), which argues that progressive branding played a huge role in Liberal party operations. This, Lukacs contends, masked a neoliberal policy assault which in some ways went even further than Conservative initiatives under Stephen Harper.

The Trudeau Formula offers an astonishingly thorough investigative overview of the past four years of Liberal governance, concentrating on key aspects: the Liberals’ failure to enact policies to address climate change; their sustained effort to dispossess and disempower Indigenous peoples while maintaining a public veneer of commitment toward reconciliation; their failure to fulfill the promise of electoral reform; their atrocious record on arms manufacturing and sales, facilitating the use of Canadian-produced weapons in horrific war crimes abroad; and the superficiality of their gestures around immigration and refugees.

“The notion that the Liberal party is a progressive force is probably the most successful marketing operation in Canadian political history. And questioning that is Kryptonite for the Liberal party,” Lukacs explains.

Lukacs is frustrated at the way some of the 2019 election scandals have been handled by media, warning that coverage has missed some of their most important dimensions. In the case of Trudeau’s blackface scandal, for instance, English-language media rarely interrogated the ways blackface is not nearly the social taboo in Quebec which it is in English Canada, despite the ongoing efforts of anti-racist activists there. As well, the systemic nature of Canadian racism was barely broached.

“Racism is a whispered subtext that runs through so much of the policies we see from the Liberal government,” Lukacs says, listing off examples. Climate change — “it’s mostly Black and brown people around the world who are facing the worst brunt of climate change.” The “reconciliation industry” — “which has seen a superficial embrace of allyship while continuing the policies of land and resource dispossession.” The “immigration regime system, which has essentially been totally rebranded as stuffed animals and hugs from Trudeau at the airport.”

“It’s easy for Trudeau to look good compared to [U.S. President Donald] Trump,” Lukacs says. “But even on immigration, the Trump government’s policies on immigration have been modelled after Trudeau’s.” His book explores how, for instance, Trudeau’s government beat Trump to the punch in lifting the post-earthquake moratorium on deportations to Haiti.

“So that’s the conversation that we didn’t really have in this country, because the corporate media are so fixated on: ‘Is Trudeau or is he not a racist?’ I mean, all white people are racist in a settler colonial society, by dint of the privileges and power that accrue to us from the racialized organization of our daily lives. But that’s not a conversation we had. I think because the debate was refracted through the prism of the election, that’s why it hasn’t hurt him so much, and also because the mainstream media didn’t draw those connections.”

The Trudeau Formula also probes deeply into the Liberals’ embrace of big oil. Stephen Harper’s flat-out intransigence on fighting climate change drew international opprobrium and fueled large-scale domestic opposition, increasing pressure on large energy companies. Trudeau preferred a more subtle approach: pitching a national energy strategy as part of the fight against climate change, bringing advocacy groups on-side; and then allowing that strategy to be taken over by the oil lobby and become a vehicle for expanding pipelines.

“All of the big oil majors actually have much preferred the Liberal party and have funneled their policies through the Liberal party,” he says. “And yet we’re still stuck with this narrative that helps the Liberals entirely, that big oil’s preferred party is the Tories. But this is not true. They’re small oil’s party. Big oil prefers the Liberals.”

The Liberal government has also come under fire during this election for its decision to challenge a recent ruling by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. The government was ordered to pay billions in compensation to Indigenous children removed from their families as a result of a dysfunctional child welfare system. Yet Lukacs observes that this is, in fact, the eighth time they’ve refused to comply with the rulings, which have been coming down since 2016. Canadians just weren’t paying attention the way they are now, he says.

This also fits with Trudeau’s formula: public avowals of respect for Indigenous peoples while working assiduously to persuade Indigenous groups to agree to extinguishment of their land rights, a process Lukacs explores in a lengthy chapter of his book.

As Lukacs observes, Indigenous youth invited to the many gala meetings and summits held by the Liberals were among the first skeptical voices in the country to publicly reject the Liberal charm offensive.

“I think in part because Trudeau’s reconciliation shtick has been unravelling in the past year — especially since they dispatched heavily armed police to dismantle and arrest the peaceful Unist’ot’en blockade in northwest B.C. against Gaslink — we’ve seen that carefully cultivated public image unravel.”

Lukacs feels that one way to defeat the Liberal formula is to shine a light on the contradictions between Liberal values and actions, and to make the Liberal party’s well-intentioned voters and members realize the intractable nature of its double standard.

The other way to defeat it, he says, is to provide an authentically compelling and inspiring alternative.

The final section of the book turns its gaze on the New Democratic Party. The NDP has, in recent years, been a site of struggle between those who desire a variation of Trudeau’s Liberal formula for the NDP, and those who would adhere to the party’s social democratic roots.

“Even though Jagmeet Singh has given us only just a little taste of that, there’s already so much energy around what he has given,” Lukacs says. “Imagine if he were actually articulating an unapologetically left-wing political agenda, rather than just the milquetoast socialism that we’re getting from him now. I think you would see a huge amount of latent unrest in this country be channeled into a political movement that could actually make a concrete impact.”

Lukacs is an overt supporter of a more progressive NDP; he is a co-drafter of The Leap Manifesto, a left-wing manifesto whose emergence brought that struggle to fever pitch within the party. In the book, he recounts this process in fascinating detail, noting with irony that the manifesto’s basic principles have already taken on a life of their own in the United States as the Green New Deal, embraced by Democratic politicians more eagerly than their NDP counterparts.

But for many Canadians seeking a progressive choice but fearing a regressive election outcome, the question remains: how to respond to those who argue a Liberal vote is a “strategic” vote?

“I think you can respond in a few ways,” Lukacs says. “One is that this invocation of the spectre of a right-wing threat is actually a muzzle tactic that liberal parties use. A muzzle against the left.”

He points to the Ontario election of 2018, where the flailing Liberals concentrated their attacks on a surging NDP, thereby guaranteeing Doug Ford’s Conservative win. This, he says, reveals not only the close affinity between Liberals and Tories, but also that the Liberals fear a progressive challenge to their power more than they fear the right wing.

The other response is that it’s much more accurate to think of neoliberal political parties “not as the lesser evil of the two parties, but as the road to greater evil. I think the damage in human lives that neoliberalism of the liberal centric sort has wreaked over the last 40 years has created this huge amount of grievance and pain and much of that is now being channeled by the right wing.”

Ultimately, he argues, the only way to build an alternative to alternating Liberal-Tory rule in Canada is to stop voting for those two parties. Despite his criticisms of the NDP, he feels they’re the party with the greatest potential to become a progressive electoral alternative.

“If we keep giving the Liberals a blank cheque, which is effectively what strategic voting does, then we’re not going to get there. It just demobilizes us constantly. It undermines the political confidence that we need to build among the left in this country to actually mount some kind of challenge to the establishment.

I don’t think we can do it if we keep succumbing to the strategic voting card.”

Hans Rollmann is a writer, editor and broadcaster based in St. John’s, Newfoundland. He’s program director at community radio station CHMR-FM; a founding editor and reporter with theindependent.ca, and a contributing editor to popmatters.com. His academic work and journalism has been featured in a number of national and international publications, and in 2017 received an Atlantic Journalism Gold Award.